In the spring of 1792, the Royal Navy Captain George Vancouver decided there was no Great River at latitude 46. The waves at the mouth of what we now know as the Columbia Bar were just too big. He couldn’t see it. Then Vancouver encountered the American fur trader Captain Robert Gray on April 29. The meeting was congenial but Gray insisted that he had identified the mouth of such a river at that latitude during his voyage there in May 1791 when he spent nine days trying to cross the strong current that prevented his passage. Having just sailed from there, Vancouver didn’t believe Gray, but the American captain was determined to explore his hunch.

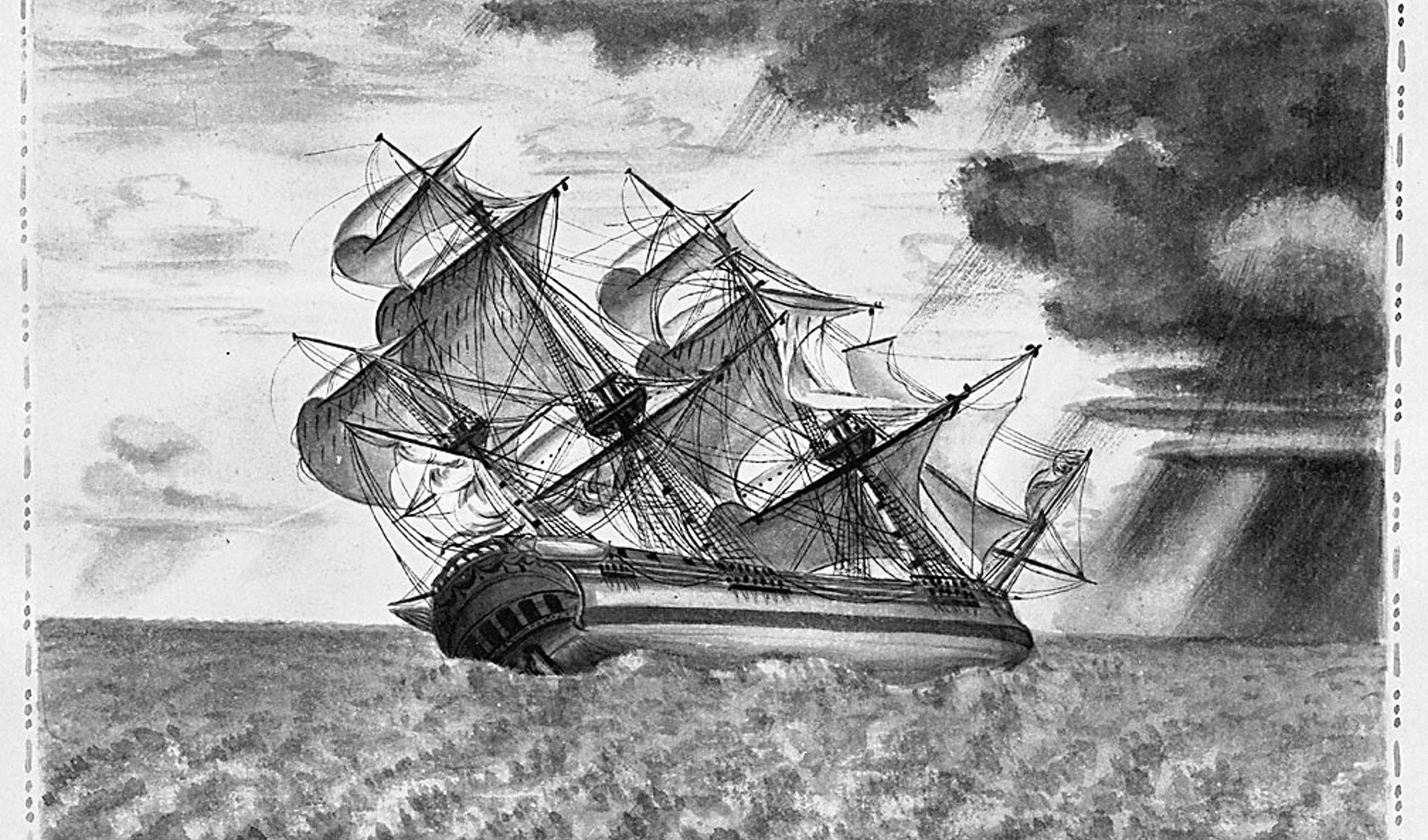

So Gray returned to Cape Disappointment and made the geographic find of the century. He crossed the Great River’s bar and named the waterway for his stalwart ship “Columbia.” [1] In sailing into the Columbia under the American flag Captain Gray delivered a new competitor into the international race for the possession of this vast region of the basin of the Columbia. For, in international usage or consideration, the “discovery” of a river carried with it at least the rudimentary title to the territory drained by that river.

Gray’s log recorded:

“When we were over the bar we found this to be a large river of fresh water up which we steered. Many canoes came alongside. At 1:00 P.M. came to with the small bower, in ten fathoms, black and white sand. …people employed in pumping the salt water out of our water-caskets in order to fill with fresh, while the ship floated in. So ends.” [2]

The Chinook name for the body of water at the entrance is “Klaát-sop.” But Gray named it “Cape Hancock,” and to the south of it across the river “Point Adams.” At the time, John Adams was Vice President and John Hancock was Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Both men received votes in the Electoral College for the first presidency of the United States when George Washington was elected and Adams became Vice President. John Hancock received the third largest number of votes after Washington and Adams.

Gray was politically astute and a loyal American, but as a merchant ship captain, his principle pursuits were to find new inlets affording desired opportunities of new contacts with the indigenous people that he might accumulate more furs for the markets of China.

Much of Gray’s official log of the Columbia Rediviva was lost but John Boit, a young officer aboard ship maintained a log of the entire voyage that survived through the centuries. As they entered the Columbia River, Boit wrote:

“The River extended to the NE. as far as eye cou’d reach, and water fit to drink as far down as the Bars, at the entrance. We directed our course up this noble River in search of a Village. The beach was lin’d with Natives, who ran along shore following the Ship. Soon after, above 20 Canoes came off, and brought a good lot of Furs, and Salmon, which last they sold two for a board Nail. The furs we likewise bought cheap, for Copper and Cloth.” [3]

From the Columbia River, Gray sailed north to engage in fur trading and he put in at Nootka Sound for repairs in July 1792. Meanwhile, Vancouver and his lieutenants were surveying inlets, bays and islands on “Puget’s Sound,” formally taking “possession” in the name of their sovereign King George. Vancouver arrived at Nootka and immediately learned of Gray’s successful search for the great river. With copies of Gray’s charts, Vancouver sailed from Nootka October 13, 1792, and proceeded toward Cape Disappointment and the Columbia River. The captain’s ship Discovery was unable to cross the bar but Lieutenant William Broughton succeeded in the smaller Chatham. Much to British surprise they found the American brig Jenny lying at anchor inside the river. Four miles from the mouth, Broughton decided to leave the Chatham and to proceed for another eight days to create his detailed charting in the ship’s cutter. He concluded his survey at Point Vancouver, a low, wooded point about two miles southeast of today’s Washougal, WA. [4]

Other explorers and traders soon followed, trekking trails along the Columbia to its mouth and the famous Cape Disappointment.

4,176 Miles from the Mouth of the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean

On November 15, 1805, the weather cleared enough for the soggy and much bedraggled exploring party of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to pack quickly and paddle to a sandy beach that faced the magnificent Pacific Ocean. To the west waited Cape Disappointment but in between lay open sea. Clark wrote:

“This I could plainly see would be the extent of our journey by water, as the waves were too high at any state for our canoes to proceed further down.”

First Lewis and then Clark took small parties of the corps on foot to Cape Disappointment and the captains carved their names, month and year on small pines. The men were astonished at the “high waves dashing against the rocks and this immense ocean.”

Clark described the country as they tramped through a rain forest of fallen “nurse” logs serving as sources of nourishment for new trees: “pine of three or four feet through growing on the bodies of large trees which had fallen down.”

Cape Disappointment, Point Adams, and the major mountain peaks had been named years before the Corps’ arrival, but they still found features they could name. Clark bestowed “Point Lewis” on a point they could see from the beach about 20 miles to the north.

The rain continued to pelt the explorers. Their position was exposed on the sandy beach that was covered with driftwood, and the shifting tides held unspoken surprises. The journals complain of stealing by native people – knives, rifles or most unprotected objects. The Corps was surprised by the high prices demanded by the Chinook in trade, and many times the captains could not afford the price.

“They were fondest of blue beads, preferring them to all other items.” [5]

Clark was attempting to trade for sea otter skins on November 20th, 1805, noting: “[they are] more beautiful than any fur I had ever seen.” He finally convinced them to trade for Sacajawea’s belt made of blue beads. Clark gave her a blue coat the next day for the loss of her belt.

The years ahead soon brought more explorers to Cape Disappointment and the Columbia River. While many looked for trade goods or riches, others sought to extend permanent roots that laid claim to international possessions. A few sought botanical discoveries that enriched the libraries and collections of the world.

End Notes

[1] See also Greenhow, Robert. Memoir, historical and political, on the northwest coast of America and the adjacent territories. Washington: Blair and Rives, 1840. 126-128. https://archive.org/details/memoirhistorical00gree

[2] Carey, Charles Henry. History of Oregon. Vol. 1. Chicago: Pioneer Historical Publishing Co., 1922. 141.

[3] The Oregon Historical Society. “John Boit’s Log of the Columbia.” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 22 no. 4. (1921): 309. https://ia801609.us.archive.org/4/items/jstor-20610191/20610191.pdf

[4] McArthur, Lewis A. “Location of Fort Vancouver.” Oregon Historical Quarterly, 34 no. 1. (1933): 31-38.

[5] Historians believe that blue glass beads, manufactured in Europe, were the most valuable among Columbia River tribes because prior to beads, native people painted garments and tents with natural dyes from nature but no natural paints held the strong blue color so highly prized by the native people.