The total solar eclipse of July 29, 1878, drew the keen attention from Native Americans and Army soldiers; Princeton professors and scientists around the world. The path of the 1878 eclipse swept from Asia across Alaska and Yukon Territory through British Columbia, down through Oregon, Idaho and Wyoming, then Colorado, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), Louisiana and Texas until it ventured into the Gulf of Mexico. Newspapers foretold its coming months in advance and the nation was abuzz with speculation. The Union Pacific Railroad touted their route through Rawlins, Wyoming, as the greatest spot to be while others looked to Denver and Central City, Colorado.

The admirals of the United States Naval Observatory consulted in May and June 1878 with the Army on duty in Montana, and deemed it best in view of the “apprehended Indian troubles,” that a station in Colorado would be safer. Naval professor Edward S. Holden originally selected Virginia City, Montana, a short distance to Yellowstone National Park, created by Congress in 1872. “Indian troubles” were fresh in the public’s mind in 1878. During the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, celebrating the nation’s 100th anniversary, the news of Colonel Custer’s total defeat with tremendous loss of life at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in Montana reached the press.

In 1877, the Nez Perce War with its sad pursuit of a small band of Native American families seeking freedom to practice traditional ways on their homelands led to the iconic public image of Chief Joseph as a brave and honorable person. General O. O. Howard and his troops crossed 1400 miles through Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Yellowstone Park and Montana. In the East, a spontaneous but short-lived American public empathy swelled for the plight of the Nez Perce. Nearly 300 Nez Perce people escaped into Canada and lived among the Sioux where they were initially welcomed by Sitting Bull as refugees. Most Nez Perce families were eager to return to their homelands and gradually warriors, women and children left the Canadian camp:

“In 1878, a group of 29 Nez Perce led by Wottolen left Canada. With the group was Kapkap Ponmi (the daughter of Chief Joseph), Yellow Wolf (who was a member of Joseph’s band), Peopeo Tholekt, and Black Eagle (Wottolen’s son). There were only five warriors in the group, each of whom had about 10 cartridges for his weapon. This small band made their way through Montana by killing livestock here and there for subsistence. At the Middle Clearwater River, soldiers from Fort Missoula attempted to block the Nez Perce passage to Idaho. A detachment under the command of First Lieutenant Thomas Wallace engaged the Indians in battle and claimed to have killed six and wounded three.” [1]

The narratives of Black Eagle and Yellow Wolf documented by Lucullus McWhorter both remark that the cover of the total solar eclipse on July 29, 1878, helped protect those Nez Perce secretly returning from refuge in Canada to their homelands in Nez Perce country. [2]

For the Bannock people, the eclipse of 1878 paid no such favor for their escape from malicious American settlers convinced that all land in the West was open and available for grazing or settlement as secured to them by the US Government. Cultivating, harvesting and processing camas was a way of life for Native Americans for thousands of years. The Bannock tribes of Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada and Oregon had avoided outright war with the Americans for half a century. Their homelands and accustomed gathering grounds including Camas Prairie in southern Idaho were believed to be secured by the [Indian] Treaty of 1869. Congress paid no attention to the misspellings in the treaty that confused the words “camas” and “Kansas.” To the Bannocks, the words sounded the same. To the Americans, few cared enough to make changes. Most settlers had passed on beyond the Bannocks’ Camas Prairie but near harvest time in May 1878, some careless travelers turned their hogs loose upon the prairie to forage to their hearts’ delight. They were soon followed by several more itinerant settlers who let horses and cattle graze upon the blue-flowered field. May was gathering season but suddenly for the Bannocks, after thousands of years, there was nothing left to gather. A series of raids unleashed outright war for the Bannocks and Paiutes and those other affiliated tribes and bands who hoped to rebuke the settlers.[3] A prompt and vigorous campaign was ordered by General O. O. Howard, Commander of the Department of the Columbia headquartered at Vancouver Barracks. Howard’s march resulted in the capture of 1,000 native people in August 1878, and soon after, the war ended with a fight September 5, 1878 at Charles’ Ford where 20 Bannock lodges were attacked, resulting in the deaths of 140 Bannock men, women and children.

On July 29, 1878, General Howard led his officers and troops in four principal columns, sweeping all the ground toward the east – toward Bannock country. Howard wrote: “I think some of the French voyageurs must have settled in this region for … everything had the word “Malheur” attached to it. There were the “Malheur” country, the “Malheur reservation,”[4] the “Malheur” river, and the “Malheur” city. … I found the [river] banks exceedingly rough and rocky, in places almost impassable for animals. … we broke away from the river, marching due east and passing over a waterless lava-rock plateau for 28 miles.”[5]

General Howard described the solar eclipse at Malheur:

“This day there was as far as the eye could reach a singular appearance of nature, owing to a partial eclipse of the sun. For a while everything appeared very much as when the heavens are obscured by the smoke of forest fires, only now the air was pure and the sky was clear. It seemed to the officers and men as if they had been suddenly ushered into another world, conceivably like that in Bulwer’s ‘Coming Age.’ In a few hours, however, the realities of things were re-established.” [6]

One of Howard’s cavalry men wrote in his diary, “Had a good view of the eclipse from the trail with my glass. Camped at Camp ‘Irving Canon’ on the Malheur.” [7] There was no indication if the man carried a smoked glass to view the sun or referenced his regular military spyglass.

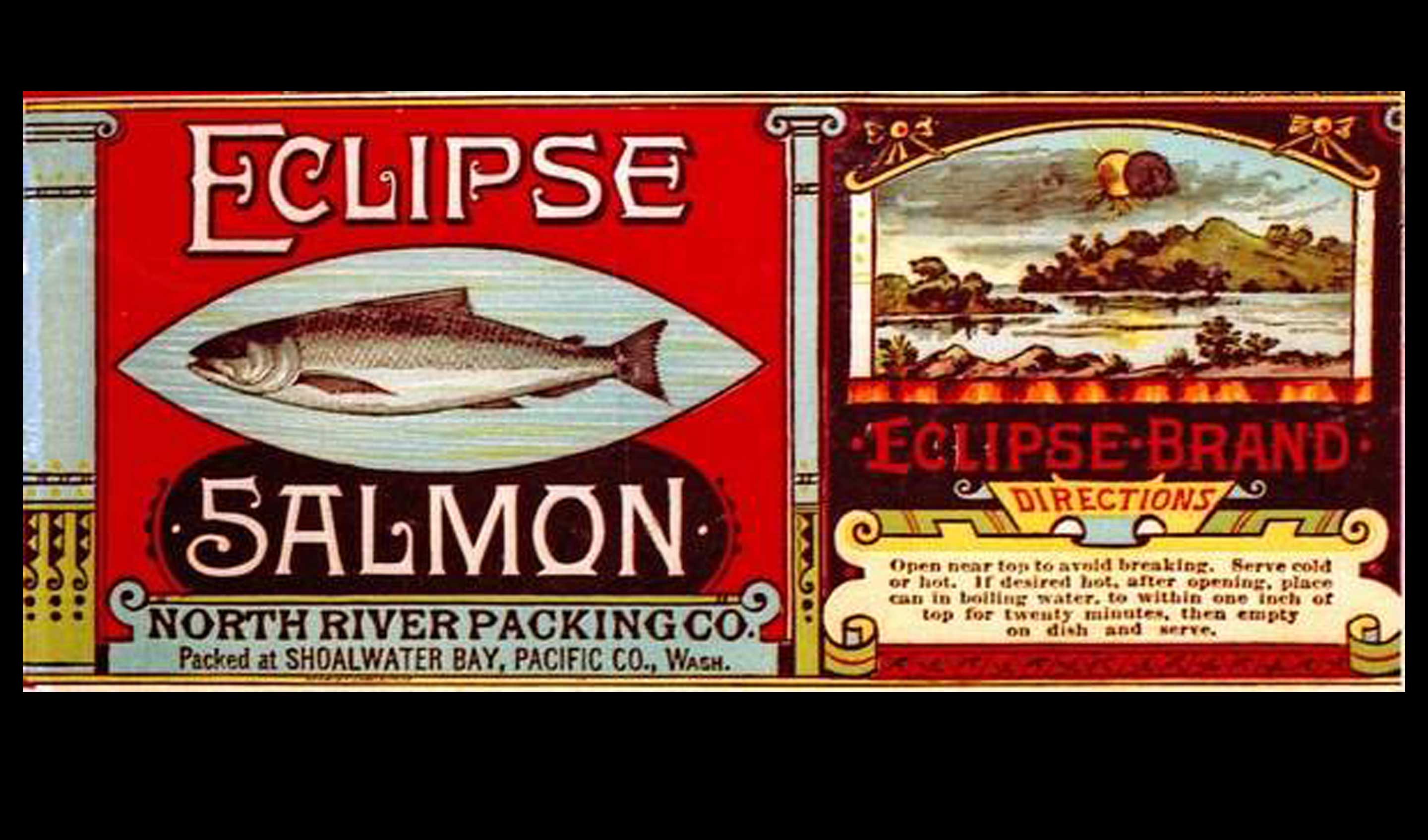

For many communities it was the first time their geographic locations had been highlighted in national news. Cannery owners at the mouth of the Columbia River used this opportunity to market their product. “The Eclipse Brand” salmon label was one of the first to be registered with the Oregon Trademarks Office in 1881, according to Matt Winters, writer for The Daily Astorian. Winters believes it’s possible the brand was pressed into use shortly after the eclipse in 1878 because it was so highly popularized by the press that year. He writes:

“Two different local salmon canneries soon began using “Eclipse Brand” labels — one like a giant black melanoma and the other a celestial waltz between sun and moon above the Shoalwater Bay wilderness.

“Up in the Olympic Peninsula town of Queets where the sun was 89 percent shrouded, a Quinault Indian quoted in the book Coquelle Thompson recalled, ‘The old people made all the noise they could. They got on top of their houses and pounded on the roofs with sticks. They shouted, shot off their guns, and beat on their drums.” It was thought the racket would scare away whatever demon was eating the sun.’”[8]

[1] Ojibwa. “The Nez Perce in Canada.” Native American Netroots. August 8, 2012. http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/1362

[2] McWhorter, Lucullus. Hear Me, My Chiefs!: Nez Perce Legend and History. Caldwell: Caxton Press, 2001. 519.

[3] Rose, Mary. “The Profound Role of Camas in the Northwest Landscape.” Confluence Tributaries: A History Blog. June 5, 2017.

[4] The Malheur Indian Reservation was an Indian reservation established for the Northern Paiute in eastern Oregon and northern Nevada from 1872 to 1879. The federal government “discontinued” the reservation after the Bannock War of 1878, under pressure from European-American settlers who wanted the land, a negative recommendation against continuing it by its agent William V. Rinehart, the internment of more than 500 Paiute on the Yakama Indian Reservation, and reluctance of the Bannock and Paiute to return to the lands after the war.

[6] Howard, General O.O. “Indian War Papers. – IX.—Close of the Piute and Bannock War.” The Overland Monthly 11 no. 1. 1888. 192.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Brimlow, George F. “Two Cavalrymen’s Diaries of the Bannock War, 1878. I. Lt. William Carey Brown, Co. L, 1st U.S. Cavalry.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 68, no.3. September 1967. 221-258.

[9] Winter, Matt. “Pacific Northwest eclipses illuminate solar system’s mysteries.” The Daily Astorian. July 3, 2017. http://www.dailyastorian.com/community/20170703/pacific-northwest-eclipses-illuminate-solar-systems-mysteries