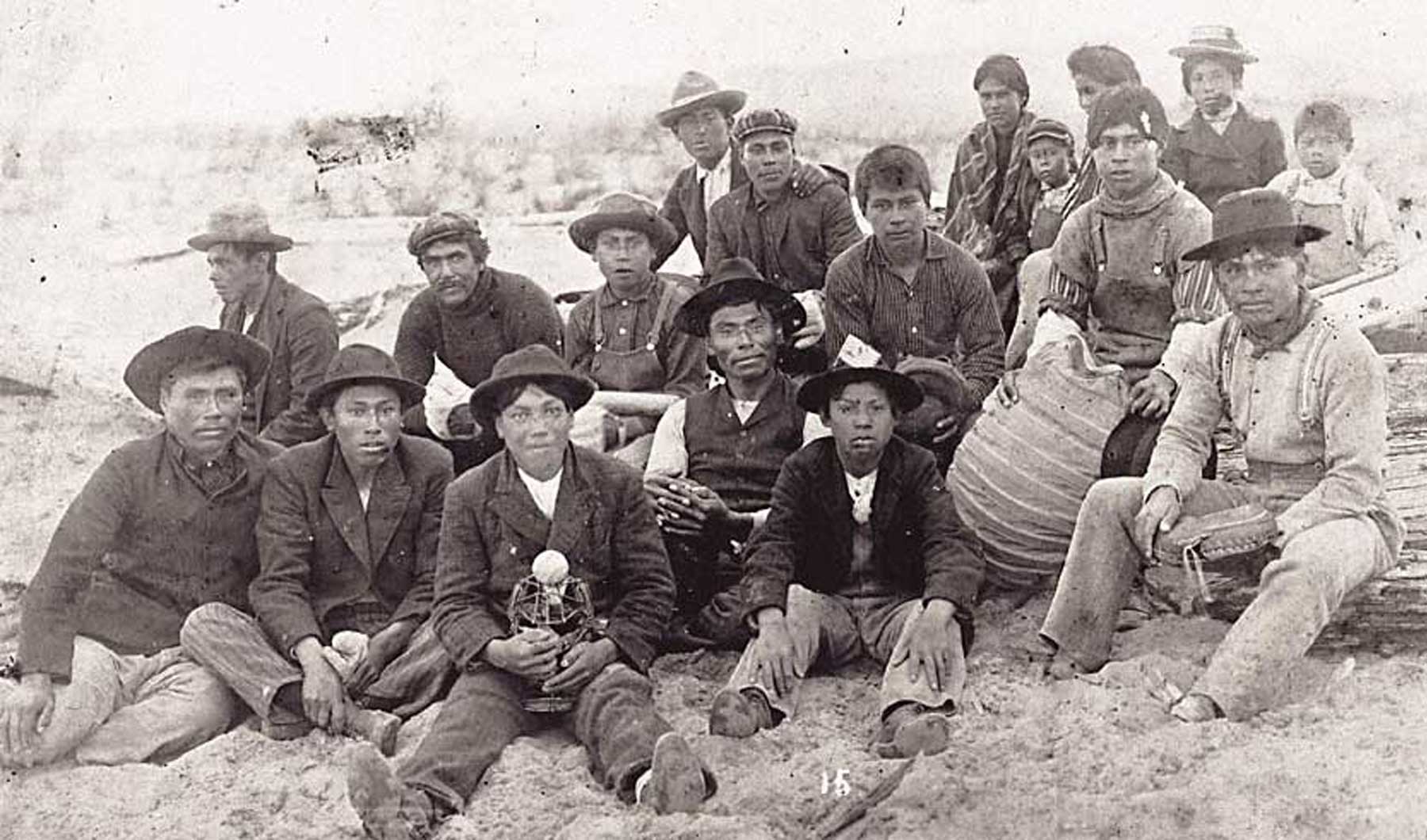

People

The Chinook are a tribe living on the coastal Columbia Basin in southern Washington. Captain Gray wrote of a “Chinoak” village in his early exploration of the Columbia, pointing at the modern town of Chinook, Washington. However, because the Chinook people were not recognized as a tribe by the U.S. government in the 19th century, when many treaties were made with Native people the Chinook were not allotted any land of their own.

Since 1979, Chinook tribal members have filed a series of petitions for federal recognition–so far, without success. Although recognized briefly in 2001, this recognition was revoked a year and a half later. More recently, in 2018 a U.S. District Court in Washington sided with the tribe on seven of their eight claims for tribal recognition, though no official recognition came of this ruling. Tribal leaders continue to work on gaining recognition on behalf of their approximately 2000 people.

Chinook Homelands

The Chinook tribe is actually one of several Lower Chinook tribes who spoke Chinookan languages. Chinook people lived along the final stretch of the Columbia River, along with neighboring Lower Chinook peoples–the Clatsop and Cathlamet. The Chinook tribe is based as far west as the Washington coast goes, right at the river mouth on the Washington side.

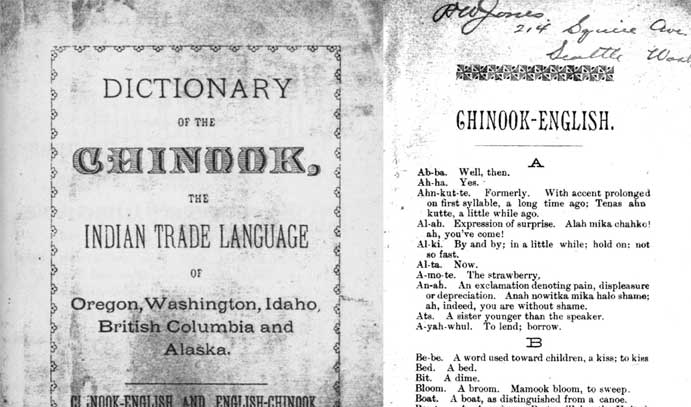

Excelling in both canoe navigation and trade along the river and coast alike, Chinook people led trade historically between native people upriver, and into Alaska along the Pacific Coast. This vast network used a trade language known as ‘Chinook Jargon,’ made up of words from several native and European languages.

Change among Lower Chinook peoples

During 19th century settlement, when a few reservations were created in Western Washington, many Chinook people were pushed off their lands. With no Chinook reservation, some became affiliated with other tribes. Some Chinook people moved north to join the Quinault Reservation, while others joined the Shoalwater Reservation, on the north side of Willapa Bay. Some chose to stay home, and continue fishing. Their descendants in the area are the people now working for tribal recognition. These Chinook people have maintained a tribal identity, despite many having moved away. Tribal leaders working for federal recognition believe that with a land base, some of the scattered Chinook families would return.

The Corps of Discovery noted about 400 Chinook people living near Cape Disappointment in the early 1800’s. Their population had already dwindled during the previous dozen or so years from smallpox and other infectious diseases they had caught from traders. During the next 25 years, the Chinook were truly decimated by disease, with perhaps as few as 30 to 40 survivors.

Chinook Trade

Chinook people excelled as traders among native peoples regionally, before they began trading with Europeans, Chinese, and others. As they traveled both the river and the coastline, they carried fish and furs between Native people in the interior, and coastal people through British Columbia into Alaska.

Their expertise in handling canoes in challenging waters allowed the Chinook to develop this far-flung trading network. Even seasoned explorers and traders were amazed to see Chinook people paddling through mammoth waves of the river estuary and ocean. Chinook men built river canoes to handle in the currents, with a broad nose and long bow and stern. Ocean canoes were built with additional boards (cutwaters) for maneuvering in the waves, by breaking through rough water.

Chinook trade with Europeans and Americans was obvious to the Corps of Discovery, as they noted some European clothing and items owned by Chinook people. However, Corps members did not recognize that some Chinook possessions were obtained through trading with distant Native peoples. William Clark made note of some ‘Chinook canoes’ and distinctive ‘Chinook basketry hats’ with a knob on top that he had not seen elsewhere. Indeed, Chinook people produced several types of canoes and basketry hats. What Clark didn’t know was that the distinctive whalers’ basketry hats, and one of the types of ocean canoes, had been made by Nuu-chah-nulth peoples on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Seasonal Cycles

Chinook people traditionally lived in winter villages of plank houses, then moved around for the summer season. Plank houses were large enough for several families to live inside, as long as seventy feet by twenty-five feet. Smoke from a fire pit cured fish almost year round, then escaped through a hole in the roof overhead. Families gathered around the fire pit, and had their own living space behind partitions.

When fish runs began with the smelt, it was time to set up temporary summer camps along the river. Chinook people made housing from bark and mats to take down and carry to the next spot. Summer season is still marked by the First Salmon Ceremony, to honor the first fish caught for the season. The first fish is roasted, divided for everyone to taste, and then its bones are returned to the river. “When that fish is released back to the river, it has the ability to go back out in the ocean and tell the other fish that we have treated it the way we were supposed to, and then the others will come in for us to harvest,” says Ray Gardner, chair of the Chinook Tribal Council.