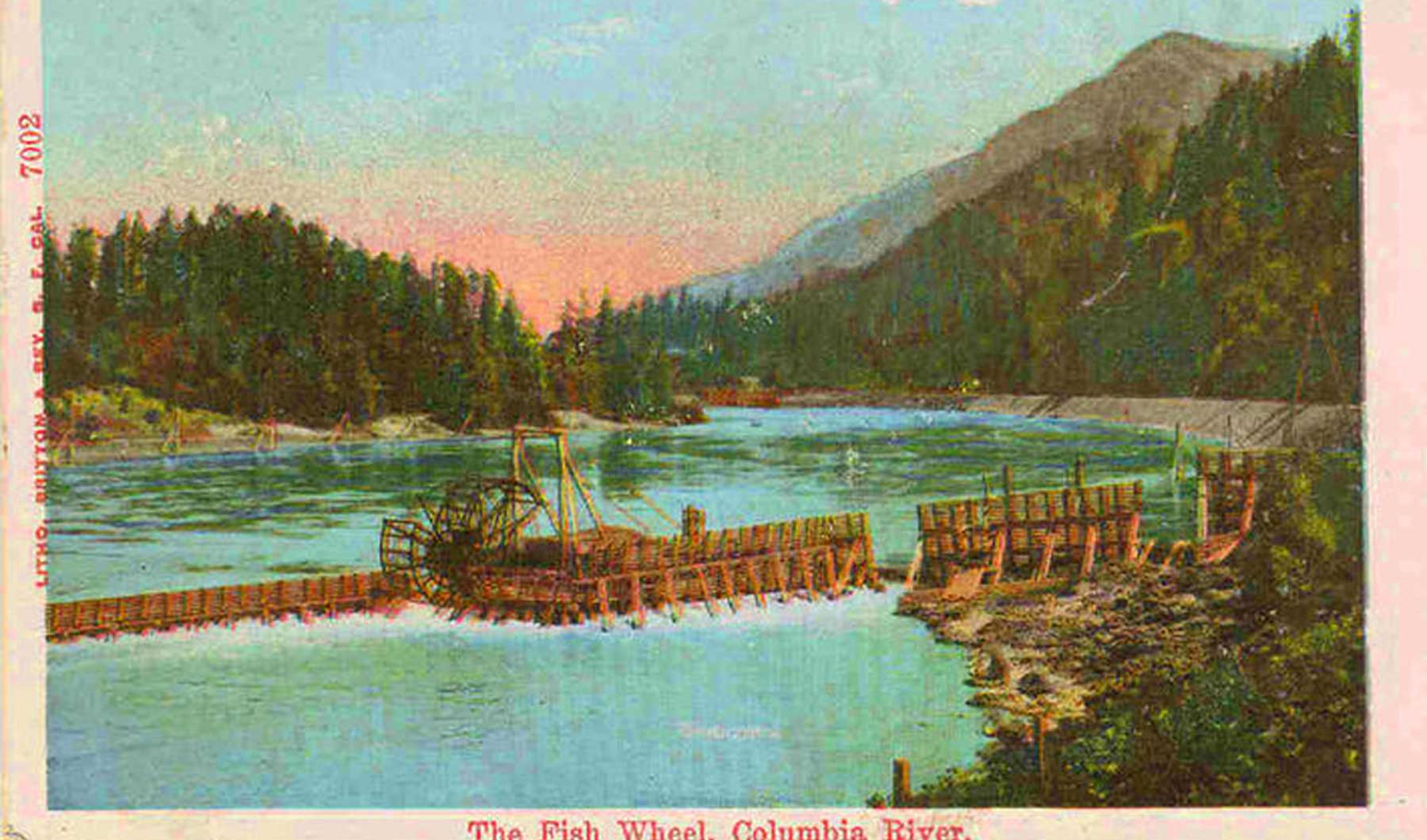

Iconic ancient fish weirs and 19th century fish wheels represent entirely different world views on what the fish and the river represent to people of different cultures. White newcomers saw the river as something to be harnessed mechanically. For native people, the river is a sustainable resource, a gift, with rules and taboos in place to protect it.

For thousands of years the 1,242-mile-long Columbia River has been central to the lives of the Native Americans who lived along its tributaries and shores. The river functioned as a superhighway facilitating trade from the Pacific Ocean to the Rocky Mountains. The river was also their supermarket providing abundant fish to support the indigenous lifestyles. And finally, the river was an important part of native spirituality.

River fish were speared and caught with nets woven of bark and grasses, and eventually fish weirs were built of slender bush branches and flexible limbs. Traditional, spiritual ceremonies were observed by most of the tribes, honoring the returning salmon by sharing the first caught and regulating the numbers to be speared or netted so that many would slip through to spawn and replenish the harvests for years to come.

Native Americans have fished the waters of the Columbia River for at least 10,000 years. However, beginning around 1800 B.C.E., when ocean levels finally stabilized after thousands of years of post-ice-age warming, anadromous fish populations—fish that migrate from fresh water, to the ocean, and back to fresh water during their life cycles—increased and became more predictably available for fishers to harvest in large amounts. Native communities of the Columbia River took advantage of the improved conditions for procuring salmon, sturgeon, lamprey, and eulachon (now commonly called smelt) by continually developing and refining fishing strategies and tools. Native fishers used a variety of resources, including wood, stone, bone, antler, hide, tendon, and plant fibers to create spears, weirs, traps, nets, poles, hooks, clubs, weights, and drying racks.

Sometimes, fishers fastened perforated stones to the bottom of fishing nets extending into the river from the shore. The nets were suspended from wooden floats to keep them taut in the force of the river’s current. These early gill nets ensnared fish by allowing them to swim part way through, then forcing them to back out of the net to escape. Once fish backed their gills into the nets, they became trapped by the net until they were removed by the waiting fishermen. Sinker stones in the Columbia River fishery were also used as anchors for boats and traps and as dragging-weights used to wear down sturgeon caught on hook and line.[2]

During the nineteenth century there was a sudden flow of Europeans and Americans, beginning with Lewis and Clark, who used the river as their highway. By the twentieth century, the Americans, who now claimed ownership of the river, looked at it in a different light. Struck by the thousands and thousands of immense fish spawning in the Columbia River, American settlers and business people sought more modern ways to capture the 50 to 100-pound fish and introduced fish wheels. The early efforts of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the 1830’s to ship salted or dried Columbia River salmon as a major export all but failed due to the proclivity of the fish to rapidly deteriorate in the wooden barrels and the horrific smell of rotting fish transported around the world.

As early as 1866, the Hume brothers of northern California located their salmon canning business to a site 50 miles inland on the Columbia River.[3] Within a few years each of the Hume brothers had their own cannery. By 1872, Robert Hume was operating a number of canneries, bringing in Chinese people willing to work for low wages to do the cannery work, and having local Native American people do the fishing. By 1883, the salmon canneries had become the major industry on the Columbia River; with 1,700 gillnet boats supplying 39 canneries with 15,000 tons of salmon annually, mainly Chinook.[4] Rumblings of the development of canneries were echoed as far north as the Canadian border due to the already limited numbers of salmon spawning in the upper reaches of the Columbia River.

Nearly obsessed with the idea of controlling and changing the natural environment, the newcomer Americans were preoccupied with harnessing the river for irrigation and hydroelectric power — building dams seemed like the most creative solution. They saw them as compliments to their engineering skills and to their manifest destiny to control nature. The dams generated electricity which helped the growth of American businesses and contributed to the wealth of the nation. They irrigated vast stretches of sage brush and sand dunes that had lain fallow for centuries. “Progress” inhibited the natural fisheries of the Columbia and altered the traditional and cultural practices of all of the tribes.

Rock Island Dam (1933), built by Puget Sound Power & Light Company was the first dam built to span the Columbia River. The Bonneville Dam (1937) was the first of thirty-one federal dams built on the Columbia River and its tributaries. The dams were built for power, irrigation, and to prevent flooding. There was little, if any, concern for the impact of these dams on the economic, social, cultural, and spiritual lives of the many Indian nations located along the river.[5] To quote the 1938 brochure for the Columbia Gorge and Bonneville Dam: “Where the West’s scenic center becomes the nation’s power center.”

End Notes

[1] Ronda, James P. Lewis & Clark among the Indians. Down the Columbia. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

[2] Oregon History Project. “Sinker Stone, Columbia River.” March 17, 2018. https://oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/sinker-stone-columbia-river/#.WKDPBW8rKM8

[3] Northwest Power and Conservation Council. “Columbia River History: Canneries.” March 19, 2012.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ojibwa.”Indian Prophets, 1800-1850.” July 30, 2012. http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/date/2012/07