Pollution, Blackberries, and Dams: The Sandy River Delta

Imagine weeding 1500 acres of blackberry brambles. That’s what it took to restore the Sandy River Delta site, which became one of the largest habitat restoration projects on the lower Columbia River. The U.S. Forest Service and its partners took on quite a challenge. It’s not only a huge area, but also one that had been degraded by industrial and agricultural use.

After the Upper Chinook were removed from their lands, the lands were converted into fish and agricultural farms. Overfishing took a quick toll on the profitability of fishing, and focus turned to other resources. The Sandy River was dammed in 1913 by Portland General Electric to form the Marmot Dam. This diverted water from the Sandy to the Little Sandy River, where a smaller dam created a lake for hydroelectric power. Poor planning meant that the Marmot Dam had a fish ladder, but fish were stopped at the Little Sandy Dam. Before water-flow regulations for dams began in the 1970s, the Sandy River was often too low for fish to go upstream.

In the 1940s, eyes turned to a useful wartime resource: metals. The U.S. government built an aluminum plant beside the Sandy River Delta, then sold it to Reynolds Metal. Waste byproducts (including metals, fluoride, and cyanide) were disposed of on site, some of it into lakes and ponds. Wastewater went into wetlands that drained into a lake, and from there into the Columbia River. Habitat and agriculture in the area became contaminated by water and air pollution.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) declared it a Superfund site and Reynolds Metals worked from 1994 to 2006 to remove toxic waste. The clean-up effort involved temporarily draining the lake to dig out toxins, and installing a groundwater extraction system. After this, Portland General Electric removed the two dams in 2007 and 2008, and dismantled the old hydroelectric powerhouse. After the dams were dynamited, the rivers quickly washed through, clearing tons of sediment. After almost a century, the Sandy River ran freely again. Salmon and steelhead quickly began retaking the newly reopened area and grew in population. However, more work needed to be done.

Habitat Restoration: Several Years of Work to Reach Sustainability

We’re moving in with tractors and starting all over from scratch – completely taking out everything that’s there and replanting with native grasses first, then trees. –Robin Dobson, U.S. Forest Service

[The site] was accessible … only if you crawled through tunnels the deer had built. The blackberry was six feet tall. –Greg Cox, Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area

When the U.S. Forest Service purchased land at the Sandy River Delta for restoration, part of the land had belonged to a cattle ranch, and its marshy sections had been drained for grazing purposes. Grazing, as it turned out, had become important to keeping invasive plants out. As soon as grazing was stopped, invasive plants such as Himalayan blackberry and reed canary grass quickly took over. Native plants didn’t stand a chance.

Tractors quickly set to work plowing through the site to remove a huge thicket of invasive plants. Volunteers, including a group of high schoolers and various members of the public who showed up for a series of work days, helped clear the land for replanting. A herd of goats was even brought in to take out invasive plants.

The Forest Service didn’t just want to plant trees. Instead, the aim was to restore sustainable native plant communities and return to a mix of woods, prairie and wetlands at the site. This required a multi-year plan. Gradually, the weeds were replaced with native plants. The site was first cultivated with oats, to continue weed control and prepare the ground for planting. Then it was time to put in native grasses. Once the grasses had taken hold, native trees and shrubs went in. Sections of land with a higher groundwater level were restored as wetlands. These areas were later marked off-limits to dogs and horses to protect the recovering habitat.

Native habitat at the delta is a mix of riparian woodlands and wetlands. A few miles east, the hardwoods give way to the conifer forests of the Cascades. The original hardwood forests were made up of black cottonwood, Oregon ash, willows and dogwoods. The delta’s wetlands were full of cattails, rush and sedges, and were critical for migratory birds and for breeding by neo-tropical birds. Waterfowl also use the delta for nesting cover during winter. The large sand deposits at the delta provided spawning habitat for the huge numbers of smelt and salmon that returned annually to the Sandy River. The goal was to restore the area to this state and to help native birds and animals thrive.

Recreation: The Community Builds a Trail

A number of interests converge at the Sandy River Delta, as it lies between three popular spots: the Gorge, Mt. Hood, and Portland. The Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area planned the site as the western entry point to the Gorge area for travelers. They also saw its future potential as a demonstration project for environmental restoration. Hikers were interested in having a good trail to follow through the restored landscape.

Volunteers built a new, well-groomed 1.1 mile long gravel path from the parking lot to the bird blind. During a three-year period, over 400 volunteers worked to clear and level the trail. Trees and taller plantings create a screen at some points along the trail. Other points are now view corridors, where long stretches of low plantings lead out from the trail. At the end of the curving trail, the bird blind is positioned at the confluence of the Sandy River’s original main channel with the Columbia River. A large group of cottonwood trees was planted to mark the end of the trail.

Some conflict arose between private property owners and fishermen, as well as other recreational users of the river. The Oregon State Dept of Public Lands determined that the Sandy River met the legal criteria for public recreational use, after studying its historical uses and the limited extent of alterations to the river. Currently, almost half of the 56-mile long Sandy River is considered wild, scenic, or recreational lands.

Confluence at the Columbia and Sandy Rivers

Artist Maya Lin and Confluence were attracted to this site partly by the large environmental restoration project near the delta, and the then-planning that was underway to remove the dams. Thanks to the involvement of Confluence, an additional five hundred acres was been restored as native habitat. A new trail led through the newly restored area, leading to an elliptical bird blind designed by Lin. A couple of people at a time can be camouflaged inside the bird blind, and enjoy looking out from an elevated platform several feet above ground level.

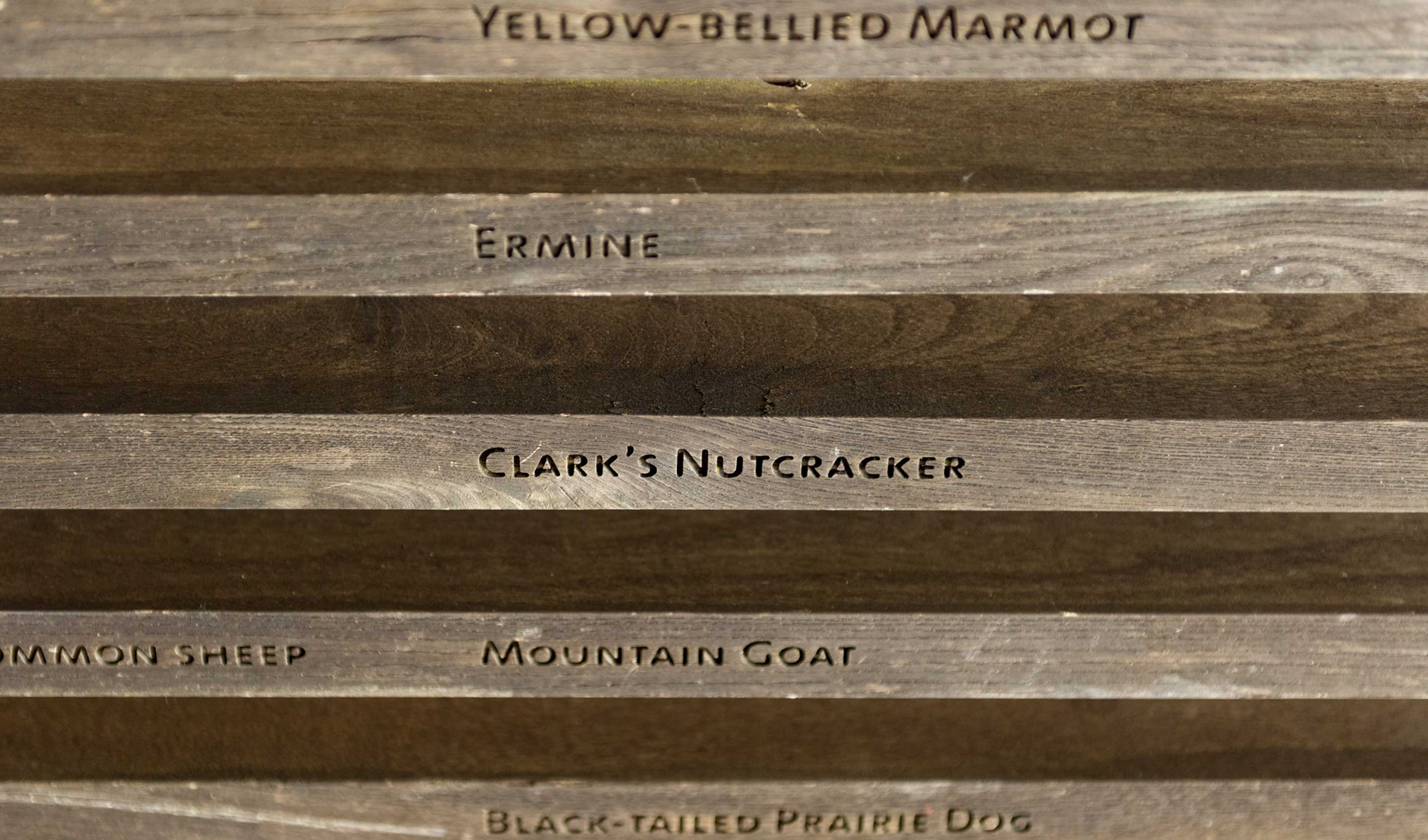

Two hundred years earlier, the Corps of Discovery had noted the great numbers of birds at the delta. Lin designed the wooden slats of the bird blind to be carved with the names of all the bird and animal species noted by the Corps of Discovery during their entire journey. While inside the blind, visitors might reflect on this record of wildlife diversity while observing any birds nearby.

Access to the site was difficult before in’s installation went in, with a dangerous highway exit (Highway 84, exit 18) and no parking. Confluence worked with the Oregon Dept of Transportation to get a new exit, and then with the National Guard to build a parking lot. About forty soldiers slept on site during construction, and a few even camped there over the weekend to guard equipment. This helped make the area much more accessible.

Confluence held a dedication of the Sandy River Delta site on August 23, 2008. Lin and project leaders gathered with the many volunteers, workers, and community members who came to celebrate.

Stewardship

Monitoring is critical for tracking the health of streams and rivers, wildlife populations, air quality, and other environmental concerns. Native plants are obviously well adapted to their environment, but restoring an area with native plants still takes time. To reach a point of sustainability where plants need little maintenance, usually an initial period of extra care and monitoring is needed to get plants established and replace those that don’t do well. At the Sandy River Delta, the large scale of the restoration project meant it was wise to begin by planting some test plots. After monitoring the test plots, the forest service could see how different plants and techniques worked at the site, and then decide how to proceed. Continued monitoring and stewardship is required to make sure that the Sandy River Delta continues to thrive for many years to come. Since the opening dedication, many people from Troutdale and from the larger area have enjoyed walking the trail out to the delta.

Ongoing stewardship is maintained by the community group Friends of the Sandy River Delta for environmental and recreational use issues.