This gallery features photographs of fishing at Celilo Falls. Fishing is an incredibly important part of Native life. Photos include spear fishing, dipnetting, fishing scaffolds, cable cars, and the drying process.

Gallery: Fishing at Celilo Falls

By Thomas Robinson

June 27, 2019

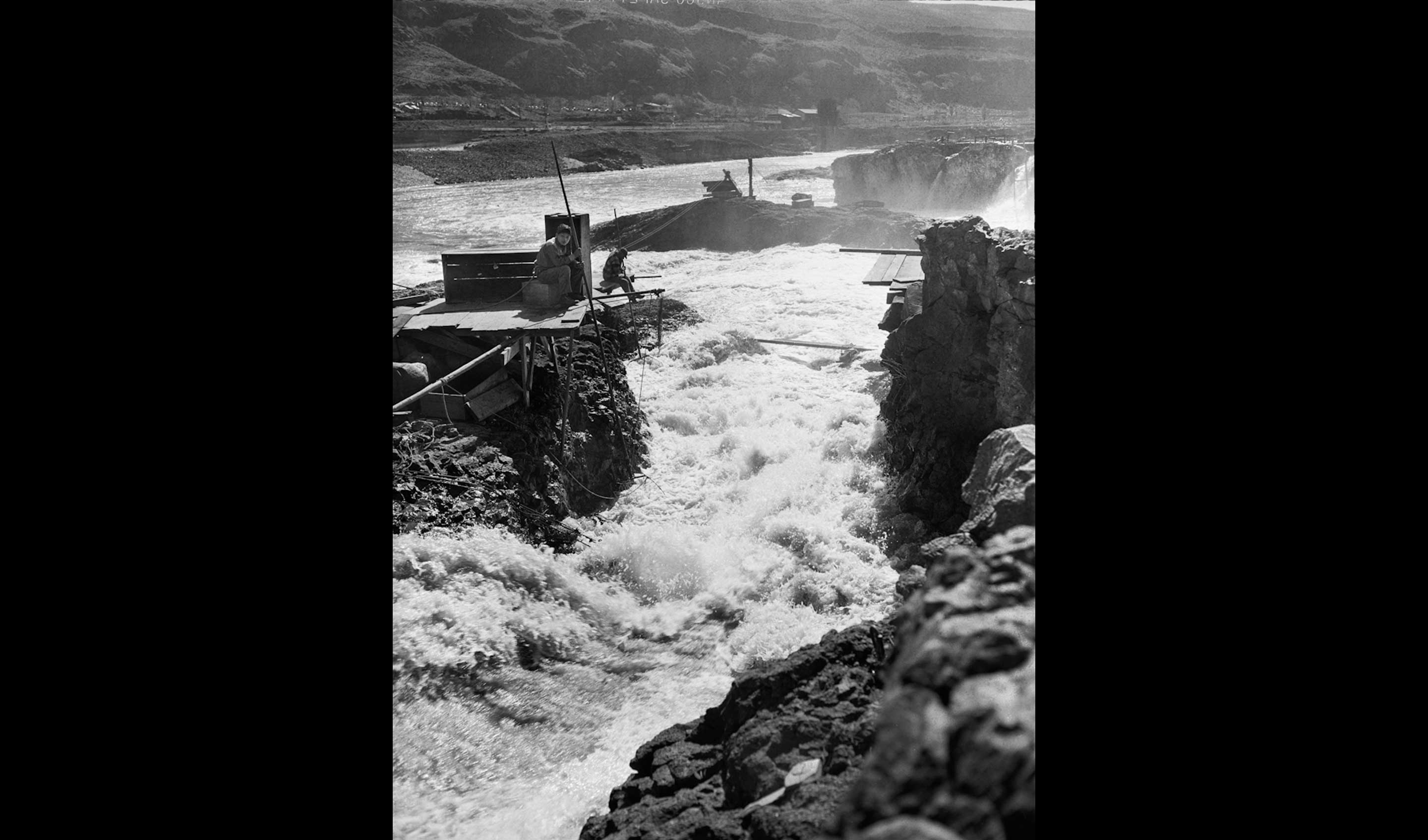

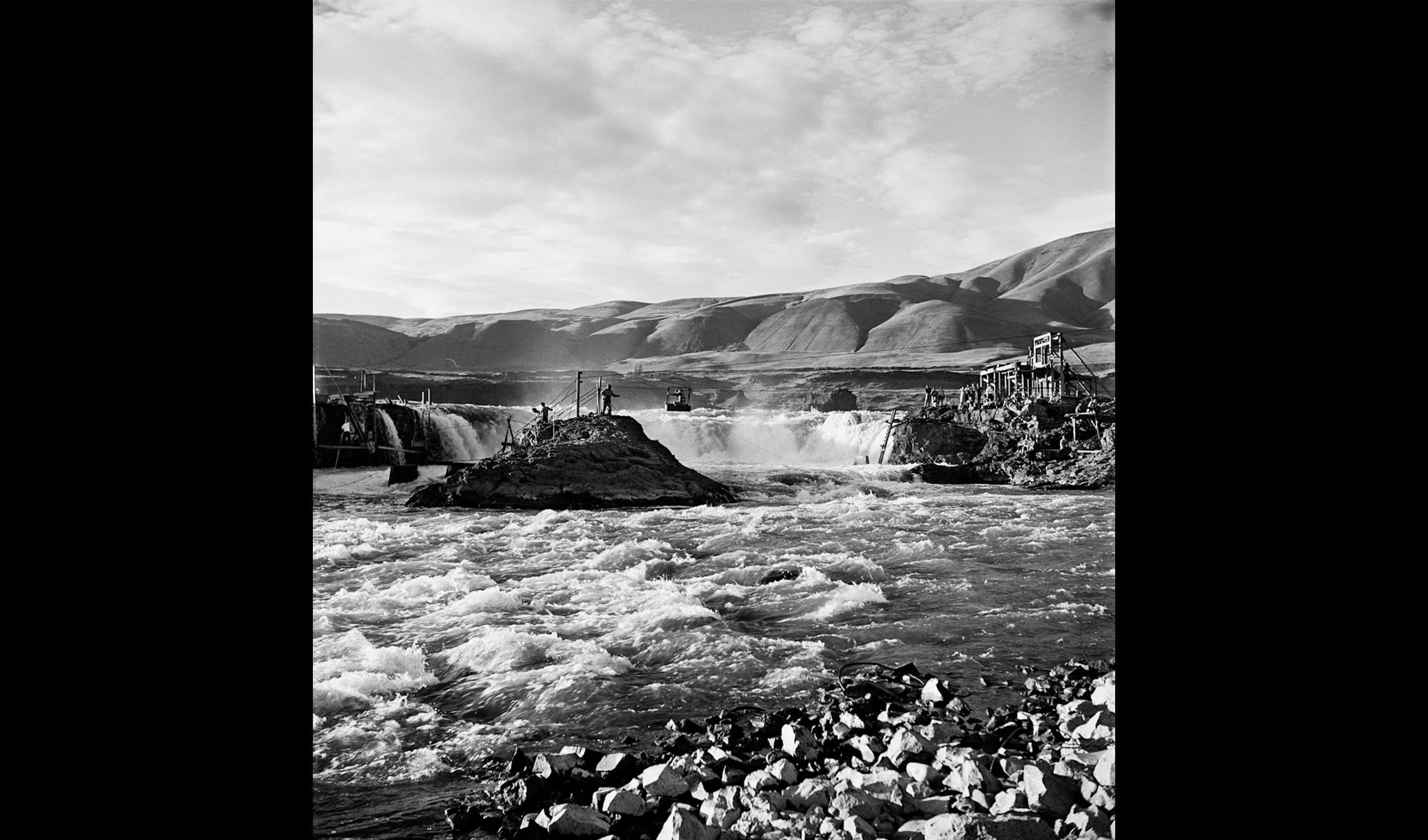

The Main channel of Celilo falls. Chief's Island on the left, Albert Brothers island on the right. This section of Celilo could be reached only by cableway cars. Before 1951

Most fishing at Celilo was done with a dip net. These worked best in turbulent water, where the fish have very limited visibility. Fish usually enter the dip net head-first. When the fish strikes the net, the net closes around the fish. The pole is lifted hand over hand up to the platform to retrieve the fish. Most Indians at Celilo used modern nets with steel hoops, the net attached to the hoop with brass rings and a thong to set the net open. This Indian is using a traditional net made with no metal parts.

Indians fishing in Downes channel at Celilo Falls, September 1953. This is a good example of the tremendous amount of amateur photography that was taken at Celilo. Lafie Foster, the photographer of The Dalles Daily Chronicle, said that in the years immediately before 1957, more pictures were taken at Celilo than anywere else in the state. This 35mm Kodachrome slide was made by a linolium installer from Portland, Constantine Zimmerman. Ultimately, the interesting composition of the photograph earned it a place in the book Wild Beauty.

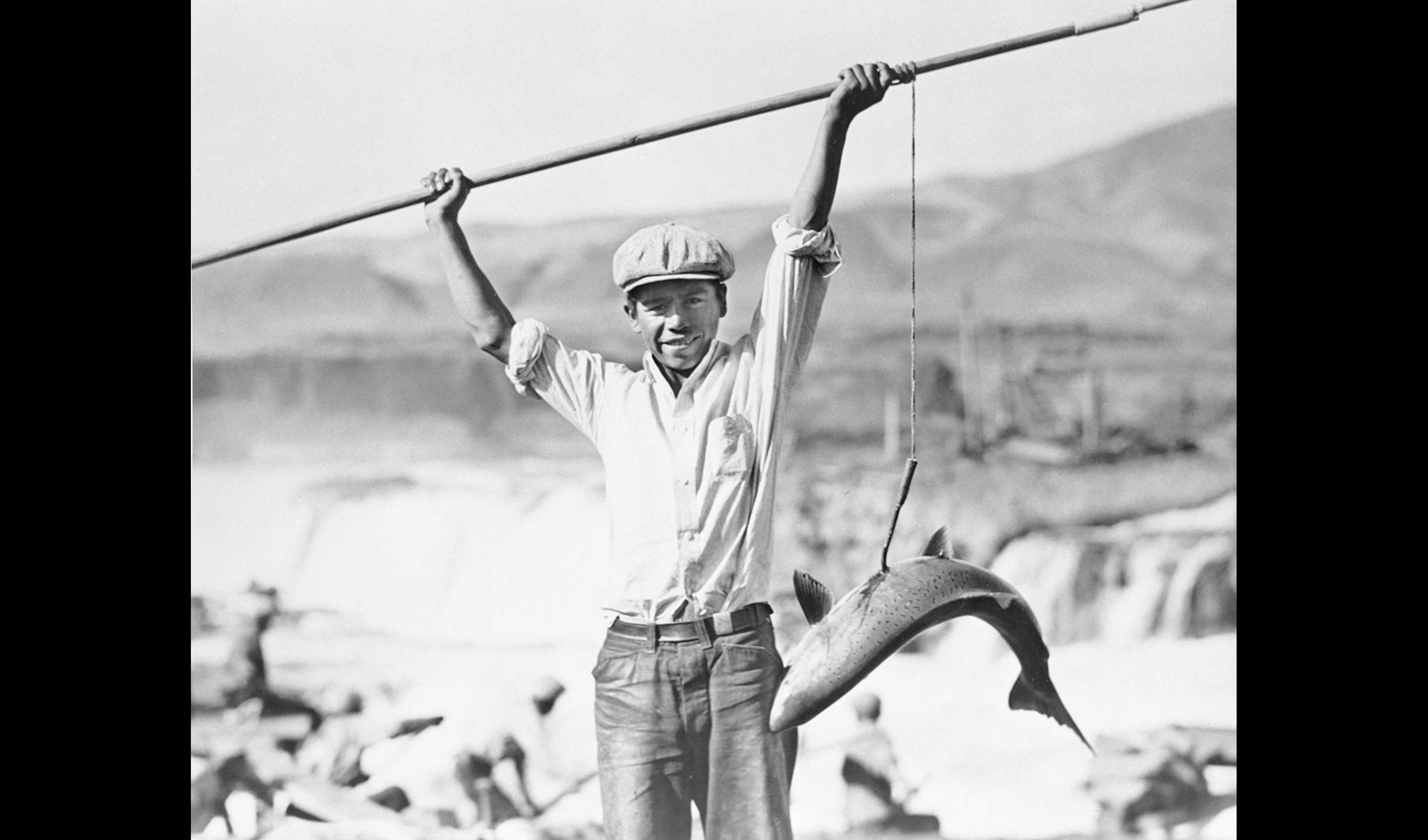

In 1941, the photographer Ray Atkeson observed this fisherman "throwing back, over a period, a dozen salmon nearly two feet long. He disdained them as not suitable for his purpose." This catch is typical of Columbia River salmon born before the dams were built. Fish were big and rich in oil because they traveled a thousand miles to spawn in Canada. The size of a fish is proportional to the length of their journey to spawn. The largest of the fish became extinct when the Grand Coulee dam was built in upstate Washington and blocked all Canadian salmon.

View from Chinook rock looking back at the crowds of tourists on the Oregon shore next to the upper cable area overlooking Horseshoe falls, at Celilo Falls, September 13, 1952

This cable car is being pulled by an engine on the Oregon shore. On the left is Chinook rock and behind it is Standing island. In the center is Horseshoe falls and behind it is the main channel and Albert Brothers island. Before 1951

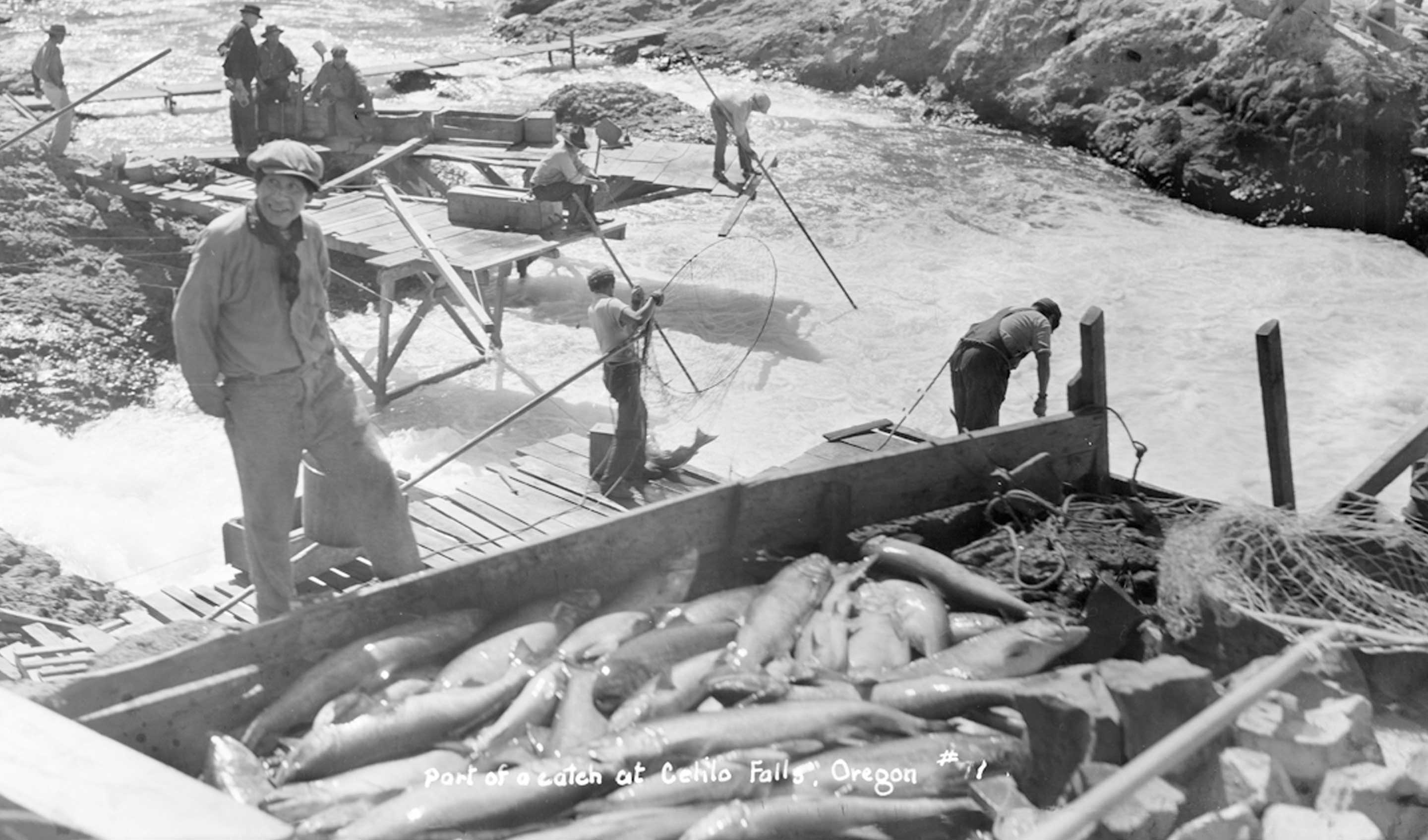

close-up of Indians' fish catch at Celilo Falls. The box is on a scaffold on the north side of Horseshoe falls. Downes channel is on the left and in the background is Chinook Rock. The box cover has been removed for photographing, fishboxes had a canvas tarp to shield the catch from the sun and wind, otherwise they would quickly spoil.

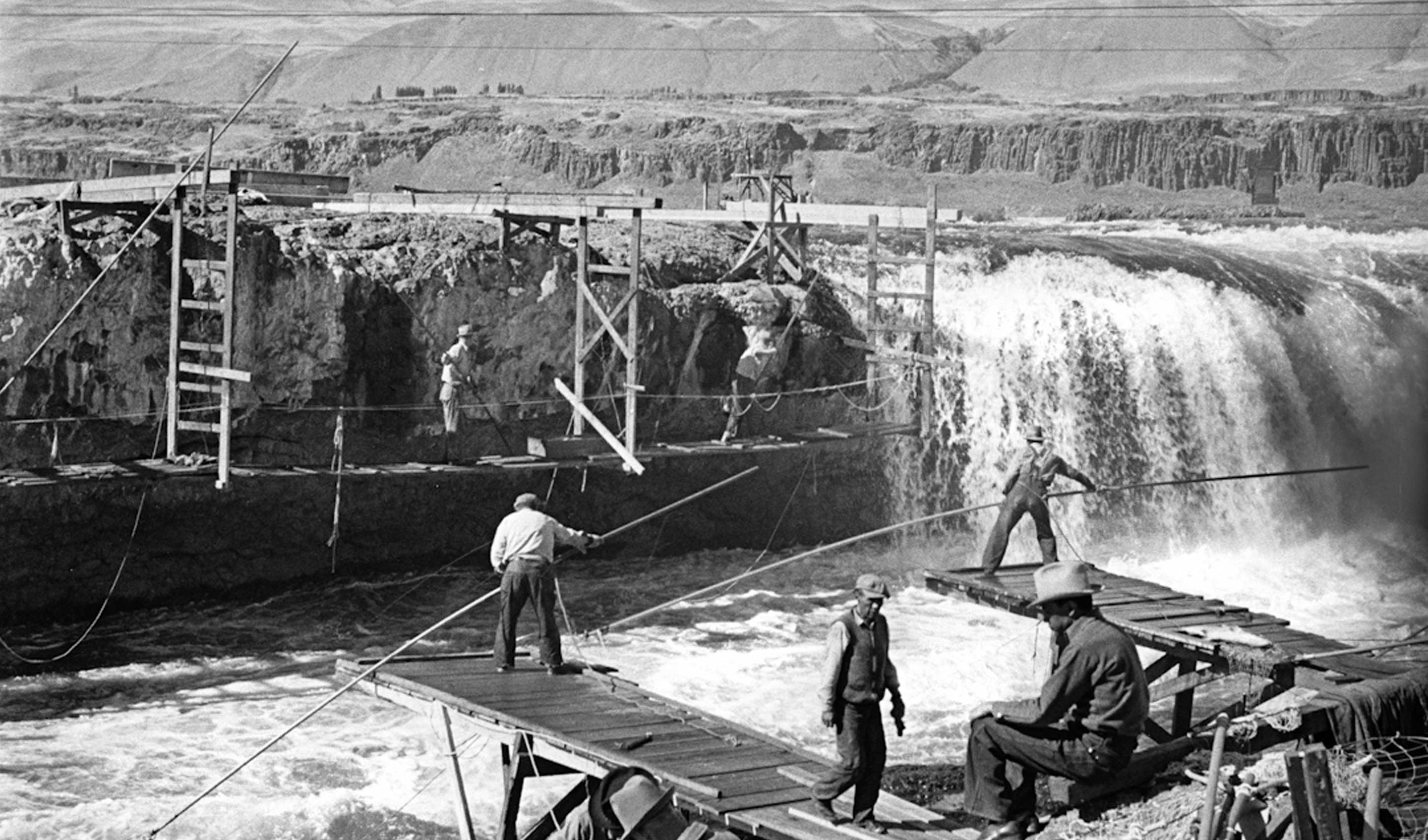

Dip netting salmon at Horseshoe falls at Celilo using stationary nets (set-dip, or bag-netting). Stationary nets were rested on the bottom of the channel to await a fish, rather than being moved to capture one. These nets were much larger and the net around the hoop was fixed open, rather than movable nets that had a thong which would close the net like a purse around the fish to prevent its escape. Stationary dip nets are much deeper than movable nets, the one shown here may be five to six feet deep. This type of net worked best when fish were likely to be caught falling back from strong currents or attempts to leap the falls. When the fish would strike the net, a vibration would travel through a string to the fisherman, who would lift the fish up quickly. This string can be seen hanging from the hoop and resting on the planks by the fisherman's right foot. The man in the foreground is Louis Jack and on the left is Joe Skahan. Photo by Ralph Gifford ca. 1940

Indians fishing at Horseshoe Falls, Celilo. These Indians are using stationary nets, rather than movable ones. They are holding the strings attached to their net to let them know when a fish lands, when they quickly pull the net out of the river. The board and pulley beside the Indian hanging over the platform edge supports the wire that holds the net hoop. May 1936

Wilson Sam with salmon on a gaff at Celilo Falls, OR, 1937

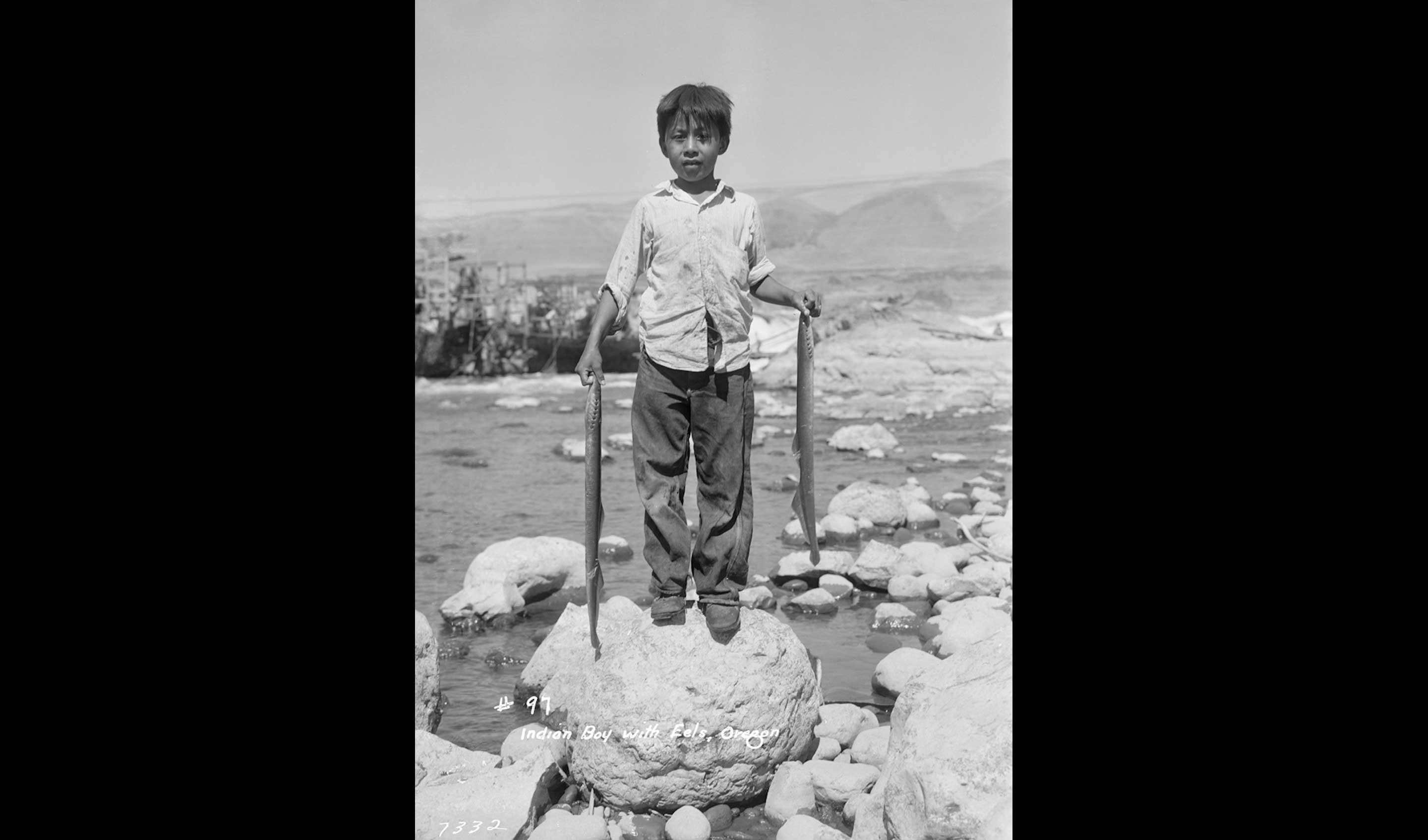

Roger Jim Sr. (1931-1988) as a young boy stands on rock posing with two large eels (Pacific lamprey). Celilo Falls in background.

3 Indians in a Seufert cable car returning from Standing island. They are being towed to the Oregon shore by a gasoline engine at the upper cable terminus. ca. 1940

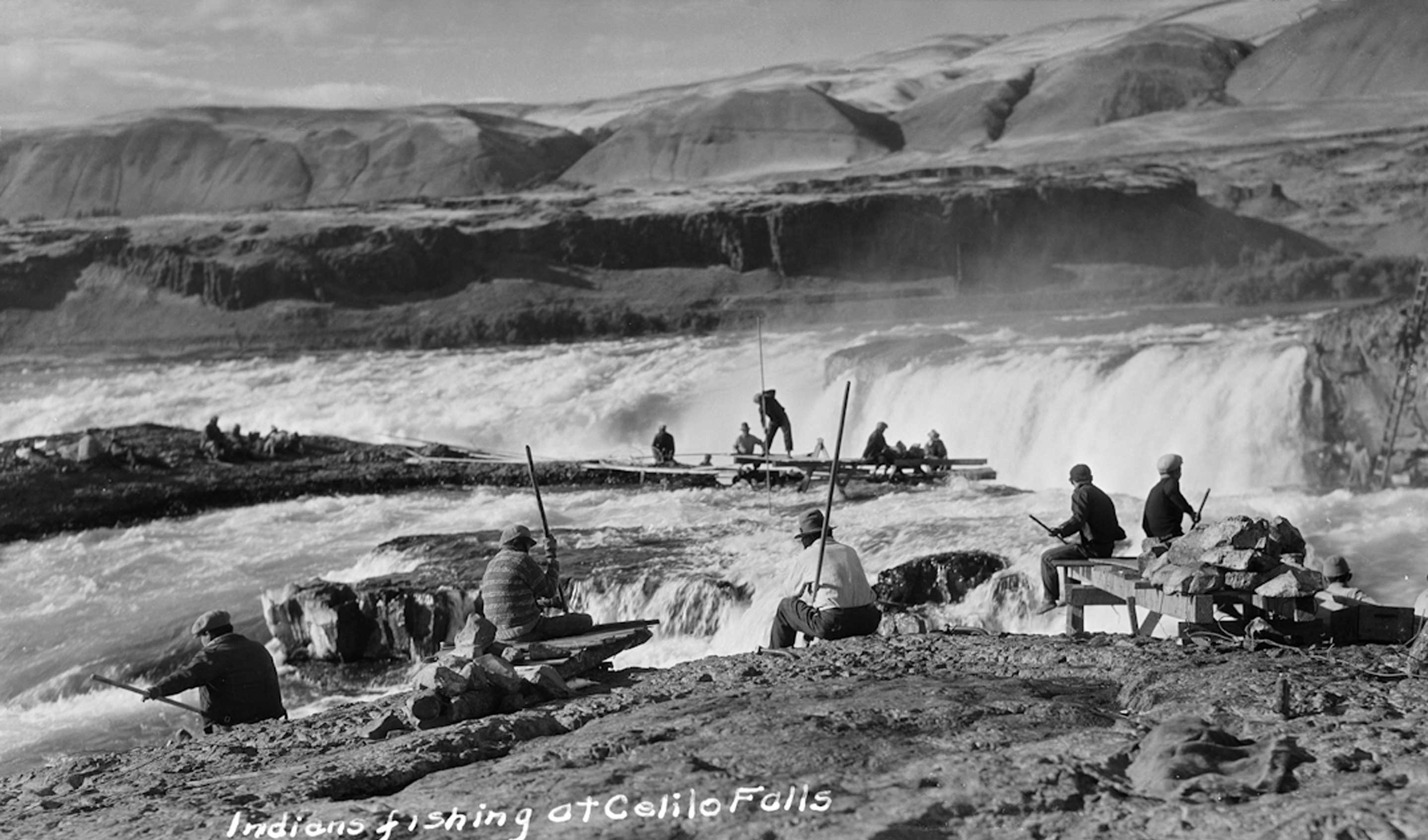

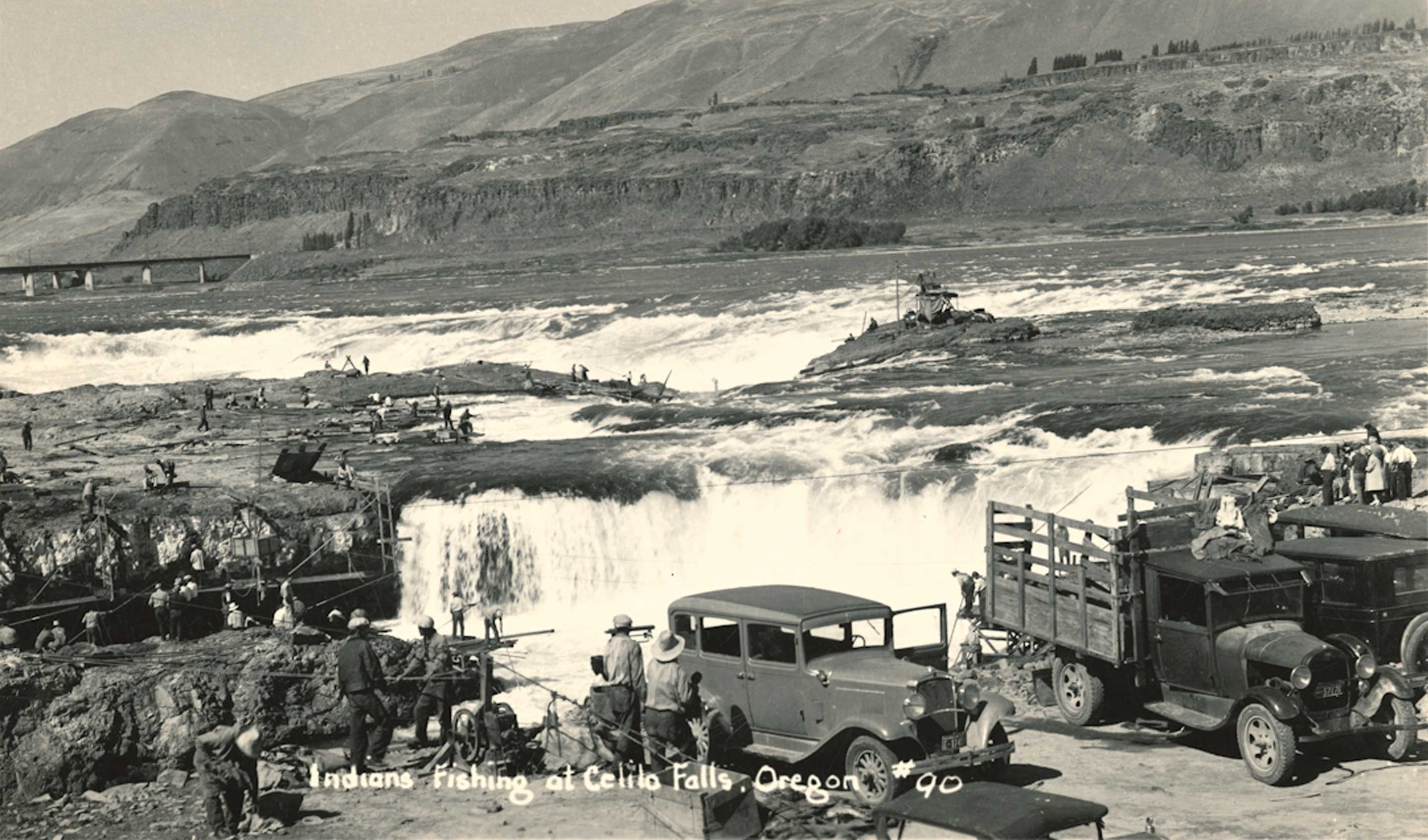

View of Indians fishing at Celilo Falls. ca, 1928

Indians fishing at Horseshoe falls, photo published in the Oregonian September 16, 1941.

Indians fishing at Celilo falls, September 1921. The conical 'Pilgrim' hats were the current fashion, inspired by the 300th anniversary of the Mayflower's arrival at Plymouth rock that year.

Indians fishing the channel between Standing and Cheif's islands, Celilo Falls. The photographer is on Standing island, across the channel is Chief's Island, behind that is the main falls at Celilo. Ateem island (later Albert Brothers island) is on the extreme right. ca. 1928

Indians on Chinook rock fishing the channel between Standing island at Celilo Falls, Oregon, fall 1936

Indians fishing at Celilo Falls. The photographer is out on an island in the Columbia river looking back toward the Oregon shore, with the Canal wall and Celilo Village in the background. 1949

In the foreground, Downes Channel meets the turbulant pool below Horseshoe Falls. On the left is the tip of Chinook rock, and behind it are fishing scaffolds hanging from Standing Island. 1956

Celilo Falls. Fishing the mouth of Downes channel. A canvas tarp has been hung over the catch box so the hot sun doesn't dry the fish out. September 9, 1956.

Indians on platforms dipnetting in Downes channel at Celilo Falls. April 18, 1948

Spearing salmon in the Long Narrows, 1901. In the 19th century spearing was the preferred way Indians fished in clear water that had good visibility of the fish. Gradually spears were replaced by dip nets made with a steel hoop and a net connected by wire rings, which would stay open until struck by a fish, which released a tonge and the net would fold around the fish like a purse. The practice of waiting for a fish to appear and catching it with a net is called roping. Most waters in this area were too turbulant or aeriated to see a fish, so neither spearing or roping was practiced as much as 'blind' dip netting. By 1939, a reporter noted that spearing was rarely used anymore and by 1950 had aparently ceased. Photo by Benjamin Gifford.

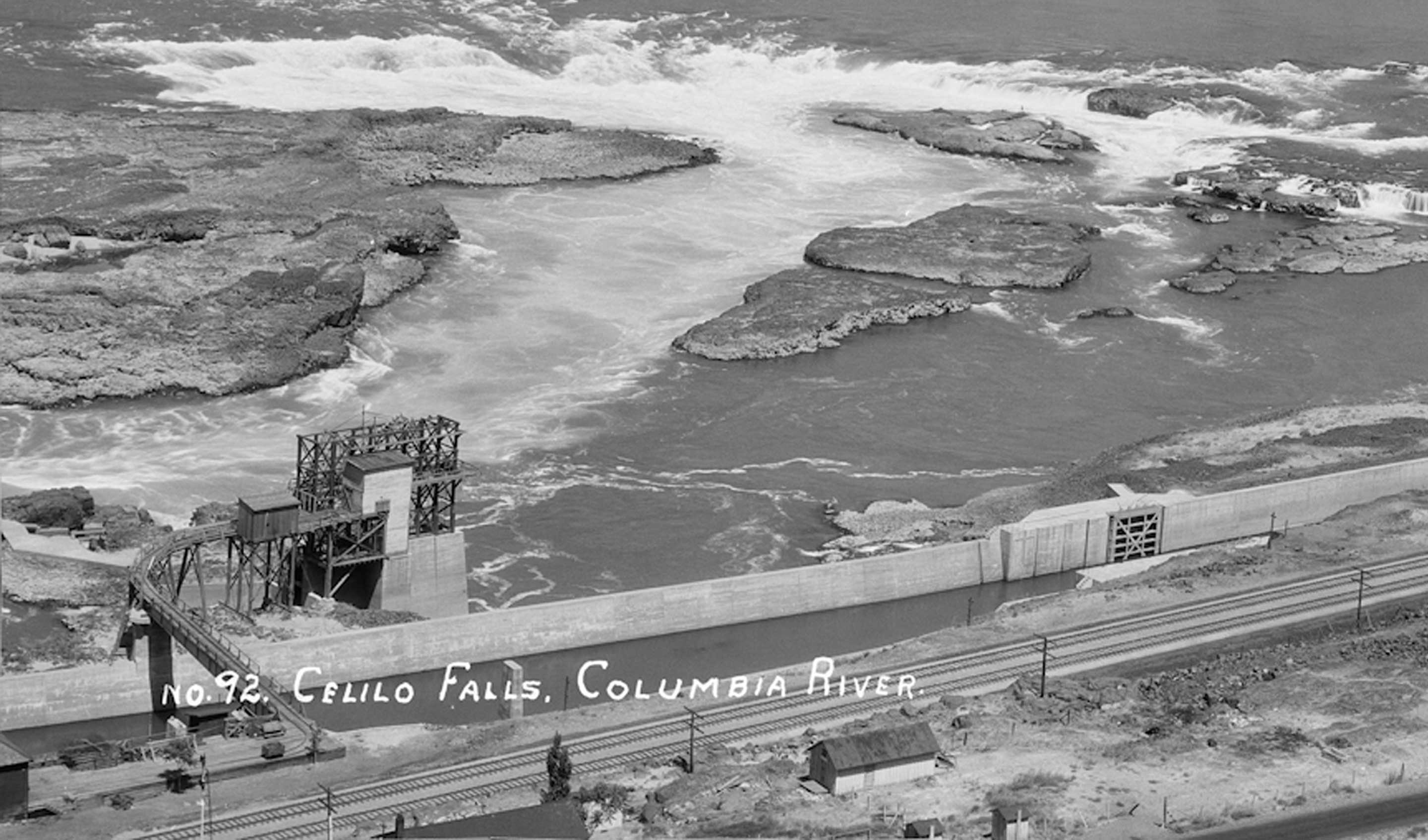

Bird’s-eye view of Celilo Falls. In the foreground is Seufert's Tumwater 1 fish wheel, with railcar siding. Behind it is Big island. The two rocks to the immediate right are Papoose island. ca. 1928.

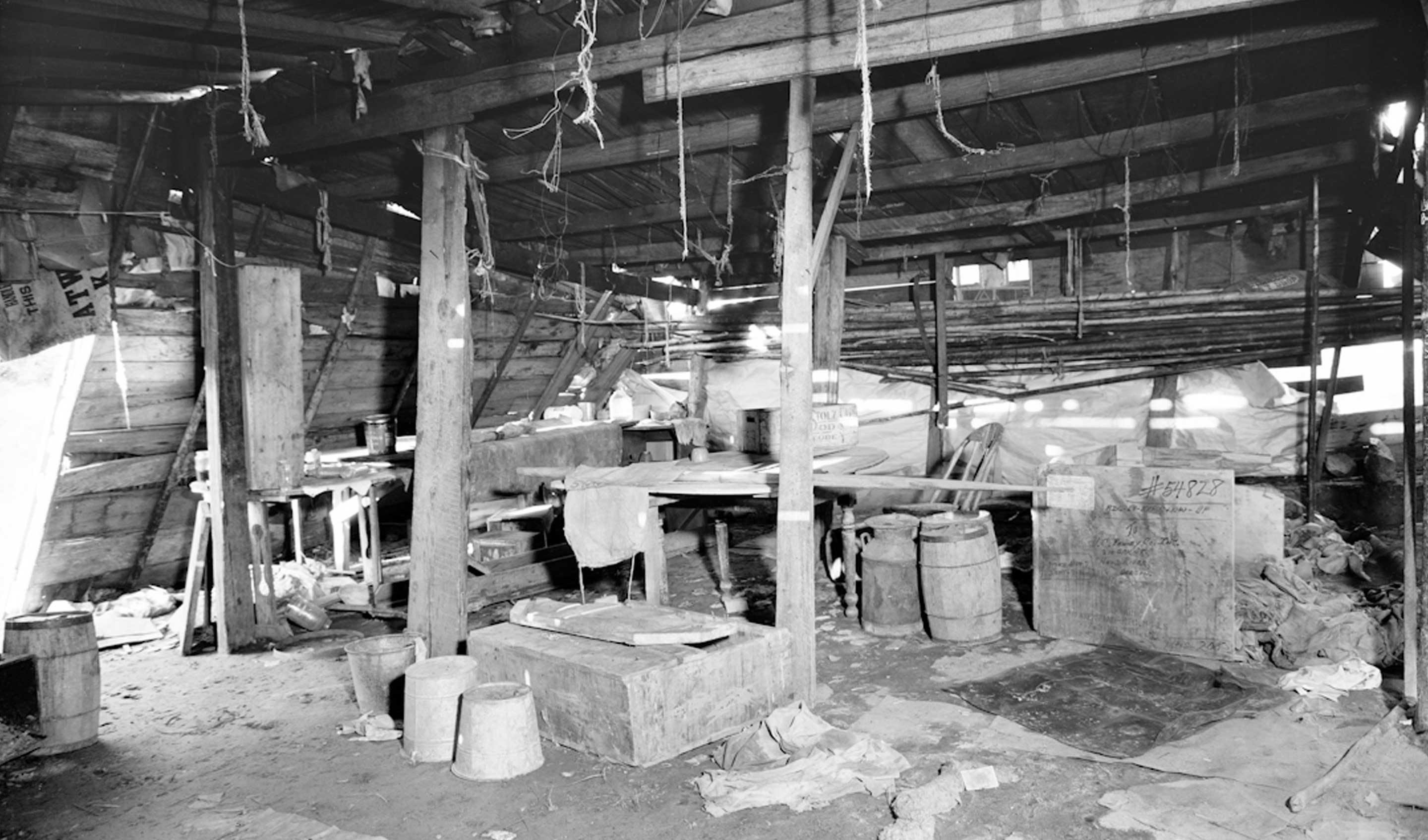

Interior of fish drying shed at Celilo Indian village. April. 1940

Edna David (left) and Stella McKinley in a salmon-drying shed, drying fish at Celilo Falls on the Columbia River in Wasco County. The salmon have been stretched on small wooden sticks and hung from poles suspended from the ceiling of the wooden building. 1952.

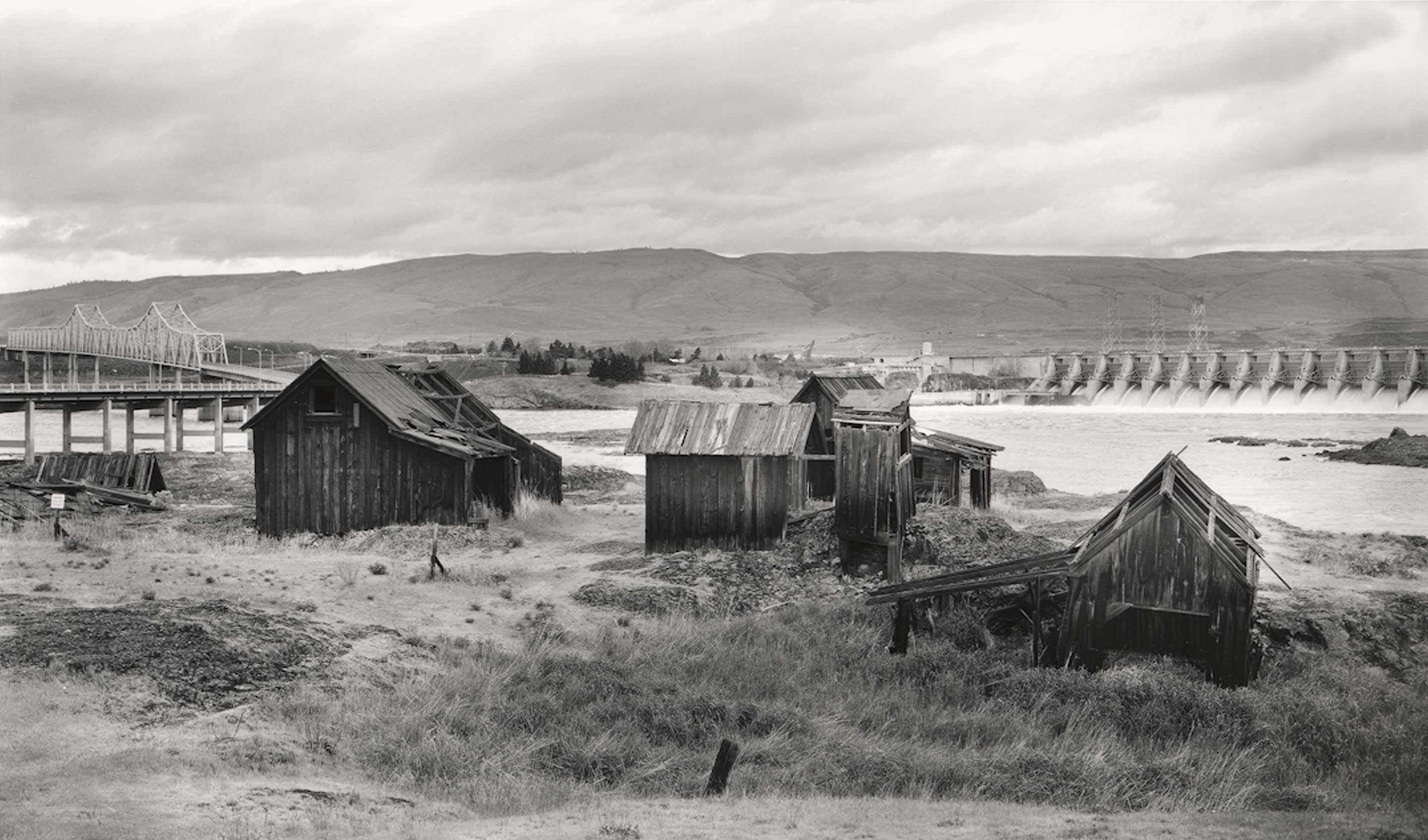

Lone Pine Tree, nestled inbetween The Dalles Bridge and The Dalles Dam, was the site of an important Indian settlement in the early 1900s. It was also the location of dispute leading to the Supreme Court decision validating Indian fishing rights in United States v. Seufert Bros. Co. 1919

The heavily fished channel between Chief and Standing islands about 1928. In the background is Ateem rock, that the Albert brothers took over in the 1930s. They were Yakama Indians that forced the Culpus family away from their traditioal site, taking over and excluding other Indians. They poured concrete forms on the rock to change the channel to their advantage as well as a base for their own cable car; Ateem became the most altered of any of the Celilo Falls fishing sites except the previously dynamited Downes channel that was enlarged in the 1880s to make room for a fish wheel. Ultimately the Albert brothers were forced to relinquish their monopoly on the island, but the dispute remained a continual crisis in Celilo for many years.

Celilo Falls was a busy industrial site that yielded tons of salmon every hour. Traffic and congestion were often heavy on the Oregon Trail Highway 30, whose two lanes ran through the middle of Celilo Indian village. With dwellings on both sides of the road, pedestrian accidents were unavoidable and frequently the victims were the very youngest and oldest of Celilo's residents. Perhaps most annoying to the Indians was the the loss of privacy and respect caused by the relentless invasion of tourists. There was nowhere to escape the hundreds of people standing above the falls or in the village taking pictures, pointing and gesturing. 1937 photograph.

Celilo in 1902. From left, Standing rock, Horseshoe Falls, Chinook rock, Taffe fishwheel, rail bridge to Taffe warehouse, buildings of Celilo (not the Indian village). Oregon Trunk RR tracks in foreground. This photo was taken ten years before the Celilo Canal was built in the area of the foreground. What follows is a contemporary description of this scene, extracted from an article in the Madras Pioneer, December 1, 1910. "The village of Celilo, 12 miles east of The Dalles, has been to the railroad world scarcely more than a flag station of the O R & N until the Hill railway system decided to span the Columbia by a steel bridge. In the commercial world it had acquired prominence through the fishing operations of I. H. Taffe, which caused him to be named one of the fish kings of the Upper Columbia. Now the post-office, the schoolhouse, the station and the dwelling house of Mr. Taffe, which formed the town, with the little brown houses of the Indians who have lived there for so many years, making their living by fishing ... Celilo has always been one of the most attractive of the many scenic spots on the Columbia, because of the beautiful falls of Celilo and Tumwater, which are just below the village ... The Tumwater falls are distinct in every way from the Falls of Celilo. They are several rods down the river from the big falls and are, seemingly, water spilling out of an immense basin of rocks where nicks have been broken in the rim. Just below these falls is seen the wooden trestle framework of the Oregon Trunk bridge with the the tramways and cars for hauling of materials for building the piers on this side. ..." The geographic names of Celilo, the falls and Tumwater, as well as the islands and channels have frequently changed over time. There is no doubt that Celilo is an ancient Indian name for this area, but nowhere does it appear on any document, publication or map until 1859. Until the 1880s, the falls were usually called Columbia falls or Tumwater falls. Celilo was the name of the railroad station and boat dock. By virtue of the word Celilo being printed on every ticket, advertisement and bill from the OR&N steamship and railroad line, Celilo came into common use as the name for the area. From the late 1880s through the early 20th century, the Horseshoe falls were called Celilo falls and the main falls were called Tumwater falls. After about 1920 Tumwater is rarely used to describe Celilo, it was in fact a duplicate name, conflicting with Tumwater near Olympia, Washington, as well as Oregon City falls which was likewise known as Tumwater. Celilo was the political name of the town comprised of a complex of buildings used by the steamship and railroad transportation companies as well as the fish operation, hotel and dance hall, and housed several hundred workers and their families, and had a Chinese section.

Overview of Indians fishing at Horseshoe falls, in Celilo Falls. Taken about 1928, before the view became cluttered with numerous cables strung between the seven principal islands in Celilo Falls. View from the Oregon shore and looking west. On the left is Chinook rock and the footbridge to it. Behind it is Standing island, Chief island and the main falls. In the center is Horseshoe falls and behind it is the Albert islands. On the extreme right, Indians are fishing in Downes channel. In the foreground are Yakama Indian fishing platforms. Every year in October these would be dismantled and stored until they could be reassembled the following year.

Overview of Indians fishing at Horseshoe falls, in Celilo Falls. Taken about 1928, before the view became cluttered with numerous cables strung between the seven principal islands in Celilo Falls. View from the Oregon shore and looking west. On the left is Chinook rock and the footbridge to it. Behind it is Standing island, Chief island and the main falls. In the center is Horseshoe falls and behind it is the Albert islands. On the extreme right, Indians are fishing in Downes channel. In the foreground are Yakama Indian fishing platforms. Every year in October these would be dismantled and stored until they could be reassembled the following year.

Indians fishing at Celilo Falls, September 1938. The cablecar line in the foreground was for a hand operated car that went from this spot on the Oregon riverbank to Chinook rock, which can be seen on the extreme left. Within two years this was replaced by a footbridge that would be reconstructed every year. This was the area that was most accessible to tourists, who were constantly walking around the rocks buying fish and the low-hanging cable line was a hazard.

View looking west at Horseshoe falls, the Main falls are behind it. On the left, the footbridge connects Chinook rock to the Oregon shore. Behind it is Standing island. The land in the foreground is the Oregon shore and could be accessed by crossing a footbridge over the Celilo canal, as the tourists in the center of the picture have done. They are buying a freshly caught salmon right off the fishing platform. The neaby Indians on the right are fishing the mouth of Downes channel.

Pulling a cable car to Chinook rock. April 19, 1953.

Looking north from the Oregon shore. From left to right, the fishing scaffolds are suspended from Standing island, Horseshoe falls are in the background, an empty cable car is waiting on its Chinook rock terminus, on the right is the Oregon shore, the upper cable car terminal and below it are Indians fishing Downes channel. October 5, 1956

Indians are fishing on Chiefs Island, without any other fishermen around. Chief's island was the fishing grounds for Tommy Thompson's family. About 1928

The Long Narrows above Big Eddy (left background, which is where The Dalles Dam is presently located). Basalt walls constrict the river to a torrential channel little more than 200 feet wide and equally deep. Photographed by Ray Atkeson for the December 1946 issue of National Geographic.

Related Content