Sacajawea State Park

For thousands of years, the desert vista at the mouth of the Snake River attracted tribes of the Plateau region for kinship and trade. People gathered there seasonally to fish, exchange goods, and to arrange marriages that helped extend families beyond their villages. The Sacajawea State Park site hosted weddings, feasts, and family celebrations for ten thousand years. It was a joyous place of kinship and culture for tribal people.

Survival in the arid, heat-parched summers and dry, cold winters, barren of game or edible plants, discouraged year-round tribal living, but a few of the Wuyukma and the Wanapums or “those who lived on the river,” extended families of the Walla Walla, Palouse, and other plateau tribes made the region their home. Salmon and steelhead runs on the Snake River were bountiful and the families dried fish and eel for winter sustenance.

Winter Home

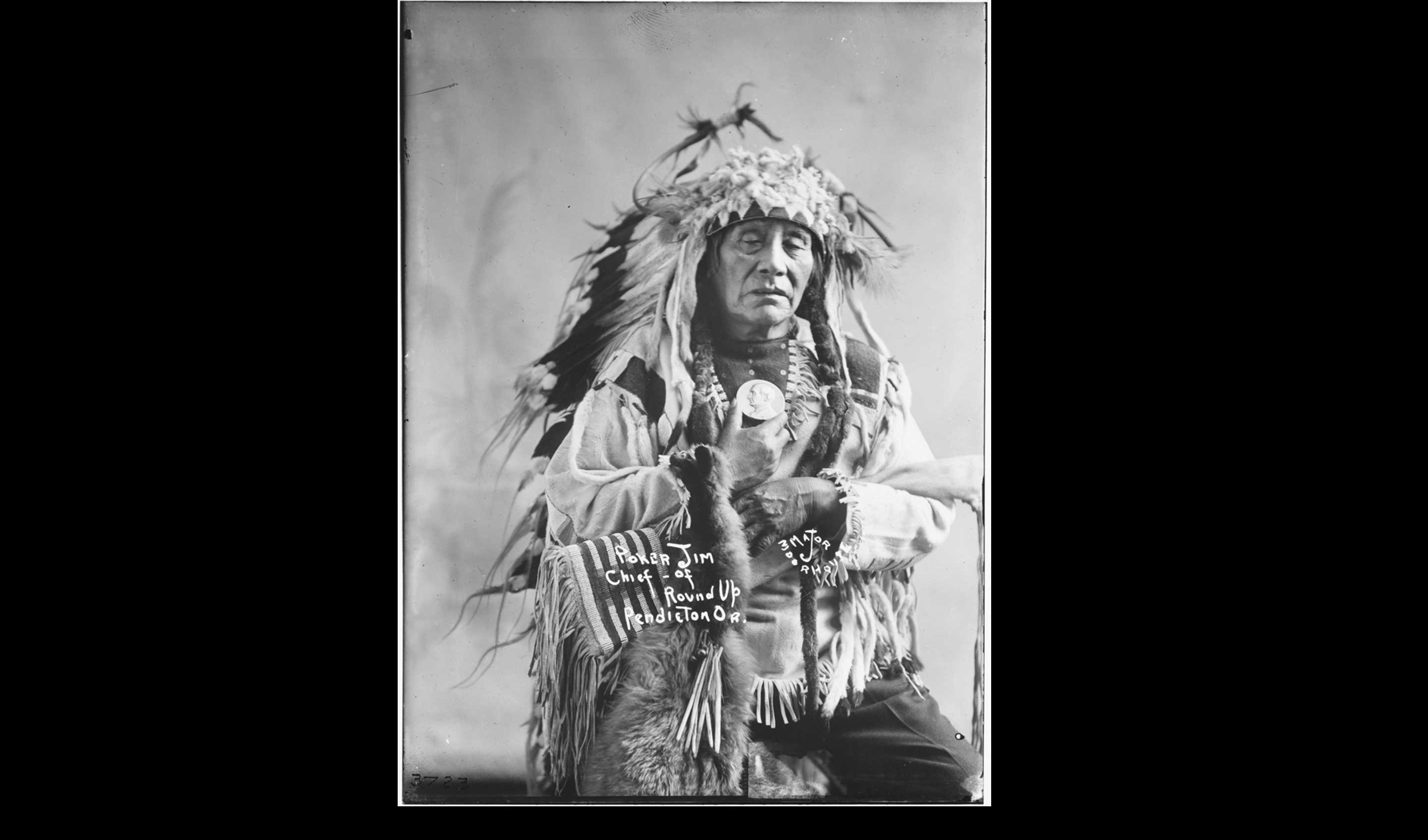

The site of Sacajawea Park flourished as a tribal ground until the Nez Perce War of 1877 when many Plateau Indians supported the right of Chief Joseph’s band to defend their homelands. By agreement of the Treaties of 1855, tribal people of the Pacific Northwest were herded onto reservations by the US Government. Those in the Sacajawea area were ordered to the Umatilla Reservation but the treaty allowed them to return to their native homeland for fishing, hunting and to gather accustomed foods. The surrender of Chief Joseph’s band in 1877 tolled the death knell for large gatherings at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers. Through the years a few Indian families managed to survive and return there, but settlers and a changing environment forever altered the native landscape and the traditional practices and rites were transformed into reservation life.

The Treaty of 1855 relocated the Walla Walla Indians to live on the Umatilla Reservation but like many others, Walla Walla Chief Homily chose to stay at his ancestral homeland on the Columbia. He accompanied Chief Moses and others to Washington DC in 1879, and their testimonies resulted in President Rutherford Hayes creating a new reservation on the river near Moses Lake, WA. It was called the “Columbia (Moses) Reservation,” but gold had been discovered there and miners were already swarming the area. Indians who tried to settle on the new reservation encountered hostility and violence soon broke out. Miners demanded the Indians’ removal and the reservation was cancelled. Many Walla Wallas resisted assimilation and like Chief Homily, they continued to maintain dual residency at Umatilla and on their Columbia River homelands until World War II.

Trade

Trade at the site afforded a lively exchange of material goods gathered by many tribes and bands from the Plateau region. Goods included horses, wood, dried buffalo and wild game, and various fruits and berries more prolific in other climes. Following the rhythm of the seasons, salmon runs afforded viable business and practical reasons for gathering at the confluence site. Families could catch upwards of one hundred salmon per day, but they needed three or less to sustain themselves. Excess fish were traded for valuable goods from other regions, some stretching as far away as the Pacific Coast. Visiting held a viable economic function as people met to plan foraging activities and redistribute food surpluses through feasting.

Women assumed a leading role in trade and kinship relations at the site. Taking stock of their winter supplies, they often determined surpluses and needs for the coming months. Women actively arranged barter exchanges and secured the useful, as well as ornamental items that ultimately decorated the garments and trappings used by their families. They were the gatherers of plants for food, basketry and medicines, many of which were traded for the goods of other regions. Women prepared feast foods for the large gatherings of families, friends and strangers and played a key role in communication among the bands as information and traditions were shared with one another.

Sustainable Practices

There are many intriguing cultural traditions of native peoples that reinforce respect for nature and its bountiful riches and also perform an ecological service. Many “first-foods” of the seasons are celebrated in sacred ceremony. The fish runs and crops cannot be harvested until the conclusion of these ceremonies, and often a special chief, such as the “salmon chief” presides over the harvest event.

Whether intentional or not, imposed temporary delays of the salmon harvests while tribal people celebrated with blessings and feasts, served an important ecological service. It allowed the upriver escapement of salmon that may have otherwise been caught by fishing nets.[1]

The first-food feasts inspired intense respect for gifts of the Creator and discouraged waste.

Explorers

On October 17, 1805, the Corps of Discovery led by Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark was successfully guided by a young Lemhi-Shoshone woman to the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers. From here the Columbia River flowed westward to the Pacific Ocean and the Corps breathed with relief that their mission would be fulfilled. Sacajawea (also spelled “Sacagawea”) ultimately ensured the survival of the explorers with her knowledge of native languages, her peaceful means of parley between different cultures, characters and talents, and as a mother traveling with a child Indians did not fear the explorers’ party.

Sacajawea’s personal history denoted a common practice among Northwest tribes – she was born a Lemhi Shoshone of the Snake/Shoshone people but she was captured at age eleven by a Hidatsa raiding party to serve as a slave. She was taken from the Hidatsa by a Minnetaree whose wife welcomed her into their family as a servant and helper. She was treated well but her captor eventually lost her in a gambling match to the trapper Charbonneau. Their first child, a son, was the infant Sacajawea carried throughout the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Although she is mentioned infrequently in the journals of Lewis and Clark, one excerpt is telling of the nature of their dependence on Sacajawea. They had passed the point of Sacajawea Park and embarked on a journey down the Columbia River in canoes. Game and food were scarce, and the explorers preferred meat or wild fowl to the constant diet of fish enjoyed by the people of the Columbia during salmon season. Seeing some Indian lodges scattered along the riverside, Clark determined to visit the tiny village. The tribal people were frightened of these stark white men in strange trappings but the three who accompanied Clark tried with difficulty to pacify the others’ fears. The Indians believed the strangers “came from the clouds” and Nicholas Biddle, an early transcriber of the Lewis and Clark journals, explained that the Indians had seen the birds Clark had shot fall from the sky and they imagined that he, too, had fallen from the sky, dropping from the clouds.

October 19, 1805: “…They said we came from the clouds and were not men. This time Capt. Lewis came down with the canoes in which the Indian[s were], as Soon as they Saw the Squar wife of the interpreter they pointed to her and informed those who continued yet in the Same position I first found them, they immediately all came out and appeared to assume new life, the sight of this Indian woman, wife to one of our interpr. Confirmed those people of our friendly intentions, as no woman ever accompanies a war party of Indians in this quarter.”[2]

Settlers

Sand and sagebrush held little attraction for early white settlers, but by 1879, American attitudes and enthusiasm were altered dramatically by the potential of railroads. The Northern Pacific Railroad selected the site at the mouth of the Snake River to build a new railroad town that would link the nation from the rail line in Montana to the Pacific Coast. Construction of this new town called “Ainsworth” commenced in 1879 and transformed nature, environment and cultural customs of the inhabitants of the region forever.[3]

On a desert plain served by two arterial rivers and their tributaries, the Northern Pacific built two sawmills to produce railroad ties and construction lumber. The unlikely location was void of trees or timber products but the vast, flat landscape became the new home of thousands of workers,[4] white men and Chinese recruited to work feverishly around the clock in the mills and laying rail track across the Northern Pacific Route.[5]

Captain William Polk Gray precipitated a flourishing steamboat trade, plying the rivers north, east, and south as log booms from Nez Perce lands on the Clearwater, the Cascade Mountains near the Yakamas and Warm Springs tribes, and timber from the Blue Mountains, home of the Cayuse and Walla Wallas, were logged, shipped, and delivered to the two mills on the desert flatlands. The once bountiful trade and kinship Indian site now held little attraction for Native Americans. Saloons and gunfights, opium dens, hotels and houses of ill-repute supplanted ten-thousand-year-old traditions overnight.

Ainsworth grew too wild for many settlers who hoped to build a permanent community and led by Captain Gray and his partners, they organized a new town named “Pasco” nearby in 1885. The school and railroad operations shifted there and the attractive idea of irrigation was introduced. Ainsworth outlived its purpose and became a ghost town, and then ruins. Hoping to attract homesteaders and even more permanent residents to the new community, The Dalles-Celilo Canal opened in 1915 with the intent of ensuring steamboat and river navigation freely from the Pacific Ocean. Fluctuating levels of water doused the great success of the canal but a pattern of interest was cast and proved the forerunner of dam construction and future development on the Snake and Columbia Rivers.

Irrigation efforts advanced in the 1930’s and soon led to the construction of dams throughout the region, generating hydro-electric power and converting thousands of acres of tumbleweeds and sand into productive agricultural lands.

End Notes

[1] Fisher, Andrew. Shadow Tribes. Washington: University of Washington Press, 2015. 22.

[2] Clark, William. Original Journals of Lewis and Clark Expedition Vol. 3. 136.

[3] Captain John C. Ainsworth, president of the former Oregon Rail and Navigation Company, was familiar with steamboats on the Northwest rivers and understood the value of linking the Northwest through transportation.

[4] Estimated at over 6,000 workers, with as many as 3,000 workers being Chinese workers.

[5] In addition to building northeast and east to a linkup with other construction forces in Montana, the railroad would connect with the Oregon Railway and Navigation Co. at Wallula. The OR&N was going into action in 1879 too, and would build down the Columbia toward Portland. Plans also were under way to build a line across the Blue Mountains, to link up with the new track on the river at Umatilla. All of this would lead to a climactic event in 1883, the arrival of the first transcontinental NP train in Portland.