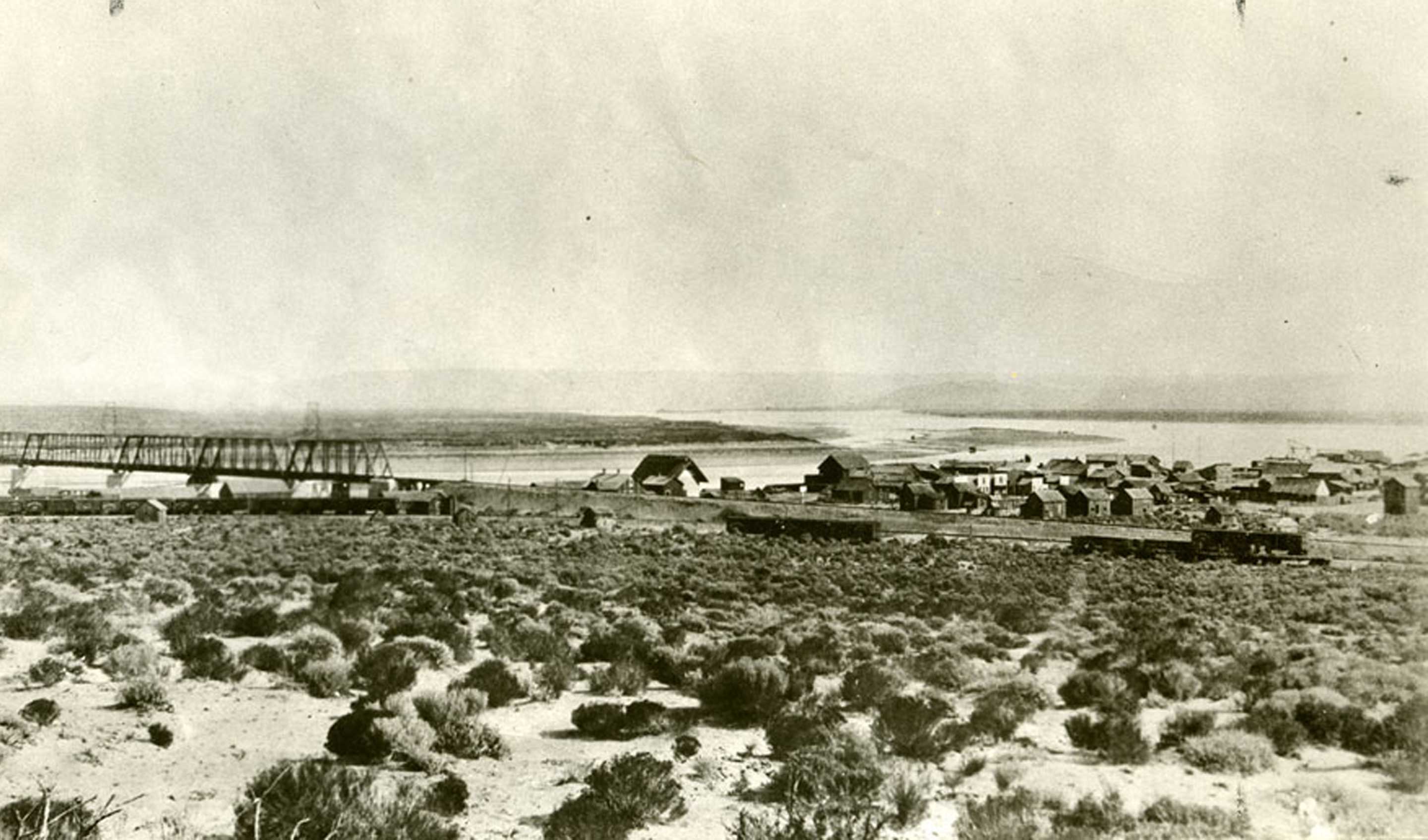

Barely a trace in the sand or sagebrush remains of the once thriving but wild town of Ainsworth, Washington Territory. Boasting a population of nearly 8000 laborers and railroad contractors by the early 1880’s, that grand metropolis was booming close to the confluence of the Snake and Columbia Rivers on a knoll overlooking the Confluence Story Circles in today’s Sacajawea State Park.

Soon after the Nez Perce and Bannock Wars of the 1870’s, developers in Eastern Washington and Oregon began to take heart that the “Indian Question” was quashed and white emigrants would soon clear the way for more ranches, towns and agricultural industries clustered around the Columbia River and its tributaries. At last, settlers believed the railroads would cross the vast prairies, climbing mountain tracks and plundering their way through the Indian reservations. After the Civil War, mining camps had sprung to life attracting hordes of single men hoping to discover their fortunes. Those who made the most money were the conglomerates who purchased or otherwise finagled ownership of rich veins of ore, and put laborers to work in return for low wages and high prices at the company store. Services for the miners – cooking and laundry – drew livable wages, too.

Sand and sagebrush held little attraction for early emigrant settlers, but by 1879, American attitudes were altered dramatically by the potential of railroads. The Northern Pacific Railroad selected the site at the mouth of the Snake River to build a new railroad town that would link the nation from the rail line in Montana to the Pacific Coast. Construction of this new town called “Ainsworth” commenced in 1879 and transformed nature, environment and cultural customs of the inhabitants of the region forever. [1]

On a desert plain served by two arterial rivers and their tributaries, the Northern Pacific built two sawmills to produce railroad ties and construction lumber. It was the future site of Sacajawea State Park and the Confluence “Listening Circles.” At that time, this unlikely location was void of trees or timber products but the vast, flat landscape became the new home of thousands of workers.

Over five thousand Chinese immigrants were recruited to work feverishly around the clock in sawmills. They also laid rail track across the Northern Pacific Route and through the Columbia River Gorge. Rails were laid from the river’s edge to haul goods and materials and a long string of railcars served as bunkhouses for the thousands of Chinese workers at the site.

Referring to the work in progress on the Northern Pacific Railroad near Ainsworth, The Spokan Times wrote in November 1879:

“White men receive $1.50 per day, boarding themselves , board being provided at $4.50 per week. Teamsters with a single team getting $3.50 per day; with double teams $5. They have all the men and teams they want at present.“ [2]

In conjunction with the activity at Ainsworth, Captain William Polk Gray [3] developed a flourishing steamboat trade, plying the rivers north, east, and south as log booms needed towing from Nez Perce lands on the Clearwater, from the Cascade Mountains near the Yakama and Warm Springs tribes, and timber from the Blue Mountains, home of the Cayuse and Walla Wallas. Forested lands were logged, shipped, and delivered to the two mills on the desert flatlands at Ainsworth. The once bountiful trade and kinship Native American site recorded by Lewis and Clark as their first introduction to the Columbia River now held little attraction for Native Americans. Saloons and gunfights, opium dens, hotels and houses of ill-repute supplanted ten-thousand-year-old traditions overnight.

Ainsworth grew too wild for many settlers who hoped to build a permanent community and in 1885, led by Captain Gray and his partners, they organized a new town nearby named “Pasco.”

The school and railroad operations shifted there and the attractive idea of irrigation was introduced. Ainsworth outlived its purpose and became a ghost town, and then ruins. The Chinese laborers had developed a series of trade shops with Chinese medicines and foreign goods but they, too, left for more prosperous communities and active work sites. Hoping to attract homesteaders and even more permanent residents to the new community, The Dalles-Celilo Canal opened in 1915, with the intent of ensuring steamboat and river navigation freely from the Pacific Ocean at least as far inland as Pasco. Fluctuating levels of water doused the great success of the canal but a pattern of interest was cast and proved the forerunner of dam construction and future development on the Snake and Columbia Rivers.

End Notes

[1] Today known as “Sacajawea State Park,” it serves as home to the Confluence “Listening Circles.”

[2] Unknown Article. Vancouver Independent 5 No. 12. November 13, 1879.

[3] Gray’s brother was steamboat Captain James Gray who operated the Lurline ferry between Vancouver and Portland in 1879. James Gray married General O.O. Howard’s daughter in September 1879. The sons’ father, William H. Gray, was the “mechanic,” carpenter and boat builder who accompanied the Whitman/Spaulding missionaries to the West in 1836.