After settlement began, not many native people–Chinook, Cowlitz, or Klickitat– remained in the valley west of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington, since it was the destination for so many early settlers.

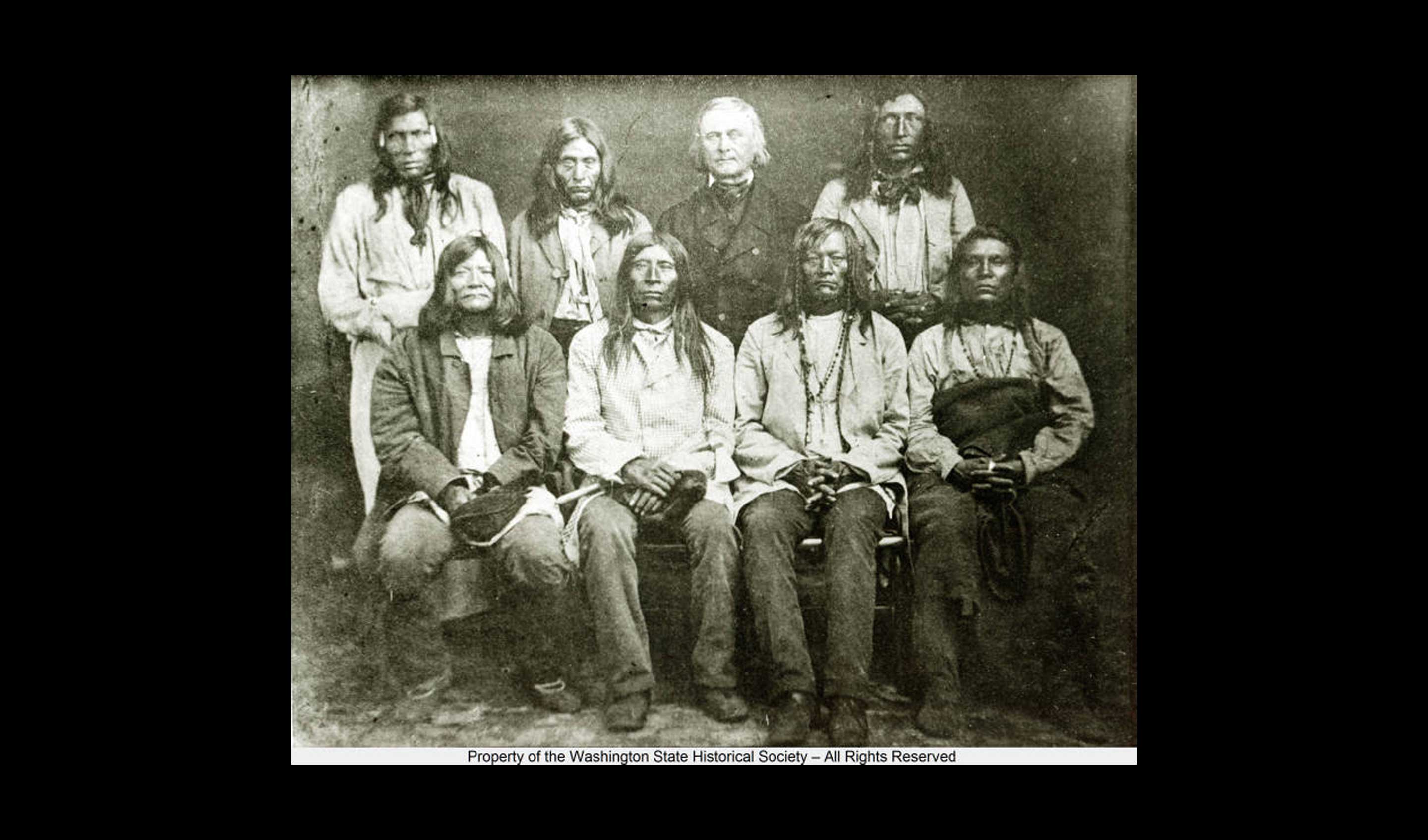

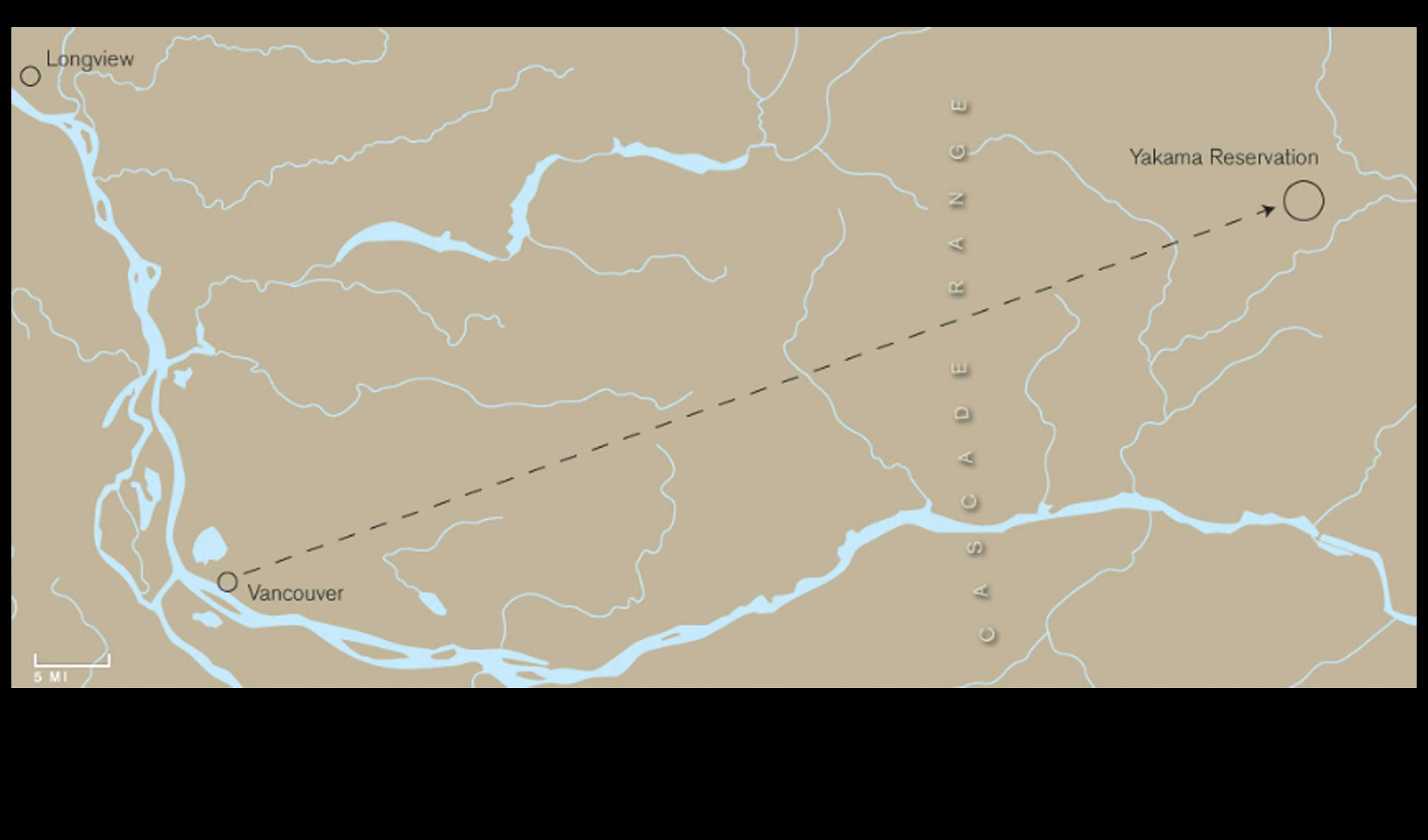

Today, quite a few Chinook people live further downriver, close to the Pacific coast. Most of the Cowlitz people now live within two hours drive of the Cowlitz River, but not directly on the river that is named after them. Many of the present-day descendants of the Klickitat people are part of the Yakama Nation. The Yakama Nation has been a sovereign treaty tribe since 1855, when the Klickitat were one of fourteen tribes that confederated on this reservation. By 1970, the Klickitat people had essentially merged with the Yakama.

Homelands: A Meeting Place for Native People

The Lower Columbia River was home territory for Chinook people, whose lives revolved around the river. Native people set up temporary camps on this site for fishing, visited to gather roots and berries, and traded with one another. The Chinook had a lot of contact here with inland native peoples, such as the Klickitat and Cowlitz.

Fort Vancouver was probably built at the end-point of the Klickitat Trail, a long network of trails and prairies through the Cascade Mountains. With the other end of the trail upriver at The Dalles, Klickitat people travelled to gather plants as they ripened at different elevations. They also traveled to exchange prairie resources (such as game, roots and berries) for fish and wapato root from Chinook people. This valley west of the Cascade Mountains had the densest population of native people north of Mexico.

The Klickitat people spoke a Sahaptin language, and lived on both the west and east side of the Cascades. Meanwhile, the Cowlitz were a Salishan people based along the Cowlitz River, east of Fort Vancouver.

The Corps of Discovery is known for the monumental journals kept by Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and four other members of the corps. Their exhaustive notes, maps, and drawings offer detailed descriptions of the geography, plants and animals, and people they encountered, and record early 19th century perspectives. On instructions from President Thomas Jefferson, a subject they documented as carefully as they could that continues to be actively documented today is Native languages. Incorporated into the Land Bridge is a Language Walk, in which the words for River, Land, and People are recorded in nine native languages of the region. Jones and Jones Architecture worked carefully with tribes to collect these words and verify how their sounds are represented accurately.

Change: A Global Village

When the Hudson’s Bay Company established their Fort Vancouver post, the site was already a meeting place of different native peoples. Mixing of peoples intensified there as a village of about 1,000 people grew by the fort. Native peoples associated with the company lived in the village alongside French-Canadian, English, Scottish, Iroquois, and Hawaiian support workers for the trading company. Through the British company’s fur trade, village residents became part of an international economy.

However, contact with outsiders was not safe for native people. At the time of early contact, native people here, as elsewhere, were overcome with smallpox, malaria, and influenza. In a span of about thirty years, nearly all native people of the Lower Columbia River died after contracting these unfamiliar diseases.

Tending the Prairies: Native People Maintain an Eco System

Washington prairies, including the Reserve, were full of useful plants. Native people cultivated and harvested about two-thirds of these plants for food, medicine, or other purposes. Women harvested and dried meadow grasses, especially bear grass, to combine and contrast with wetland plants in basket-making. Women also harvested edible camas bulbs in large enough quantities to trade. Some Native people today are introducing children to harvesting and cooking camas bulbs, to pass on this traditional food source.

A technique of regular controlled burning was used to sustain the prairie ecosystem. Bear grass, for example, depends on regular burning for strong growth, and is known as the first plant to reappear after a fire. Burning the prairies increased plant diversity, maintained open areas for harvesting, and kept visibility for hunting. Otherwise, prairies would get swallowed up by Douglas firs. The practice was ended as settlers turned prairies into farms. Today, some researchers have found that native plants get a head-start over exotic species in recovering from fire.

Lewis and Clark: “Desirable Situation for a Settlement”

The Corps of Discovery stopped at the site of the Historical Reserve. Lewis and Clark both made favorable comments about the area in their journals.

Here I landed and walked on Shore, about 3 miles a fine open Prarie for about 1 mile, back of which the countrey rises gradually and wood land comencies Such as white oake, pine of different kinds, wild crabs with the tast and favour of the common crab and Several Species of undergroth of which I am not acquainted, a few Cottonwood trees & the Ash of this countrey grow Scattered on the river bank . . . –William Clark, November 4, 1805

This valley would be copetent to the maintenance of 40 or 50 thousand souls if properly cultivated and is indeed the only desireable situation for a settlement which I have seen on the West side of the Rocky mountains. –Merriwether Lewis, March 30, 1806

Fort Vancouver: “Beautifully Situated”

The Hudson’s Bay Company decided to move upriver from their first trading post at the mouth of the Columbia. A hundred miles upriver, Company representative John McLaughlin found a sloping riverbank leading to a prairie with forest behind. The forest would provide timber, while the prairie could easily be farmed and used for pasture. Plus, the site was already a trading center for native people. Soon Fort Vancouver was the headquarters for a huge region of the western U.S. and Canada.

One Company employee found the site so attractive that it seemed as if it had been landscaped:

The Establishment is beautifully situated on the top of a bank . . . an extensive view of the River the surrounding Country and the fine plain below which is watered by two very pretty small Lakes and studded as if artificially by clumps of Fine Timber. –George Simpson, 1825

Settlement: Army Arrives, Company Goes

As more American settlers came to the region, many of them made a first stop at Fort Vancouver. At the fort, new arrivals could find out more about the area, and obtain supplies. In the mid-19th century, there was a changeover from the Fort to U.S. Army barracks. The international boundary between Canada and the United States was set at its current location, resolving the question of British vs. American territories in the Pacific Northwest. The British Hudson’s Bay Company coexisted with the U.S. Army for about a decade, then moved to Victoria, in British Columbia.

Furs were the first natural resource of the Northwest to be gathered and sold on a massive scale, and so were the first to decline. The fur trade was declining by the mid-19th century, and more settlers were farming. Outside the fort, the village grew through this change in the economy, with more employees arriving from Hawaii. Near the Army Barracks (the former Fort), the City of Vancouver grew to have lumber mills, docks and canneries.

As railroads began to cross the continent to reach the West, access to Vancouver from the Midwest really opened up. People began rushing into Vancouver and Washington Territory in 1883, since they could travel easily on the Northern Pacific Railway to Portland. Once railroads reached Vancouver itself 25 years later, its position as a crossroads between east-west and north-south routes was greatly amplified.

Challenges of topography slowed the railroads in reaching Vancouver, either through the Cascades or along the Washington side (north bank) of the Columbia River. But by 1908, a Washington rail line stopped in Vancouver. Two years later, a railroad bridge crossing the Columbia River opened. The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway then connected Vancouver with Portland and Seattle. At the time, it was the longest double-track bridge in the country.