The Salmon runs through here – from the ocean to the inland waters up to the Snake (Bannock Indians) and the Clearwater (Nez Perce) and north to the Salish (Spokane, Colville, & Coeur d’Alene Indians). -Antone Minthorn, Tribal Elder

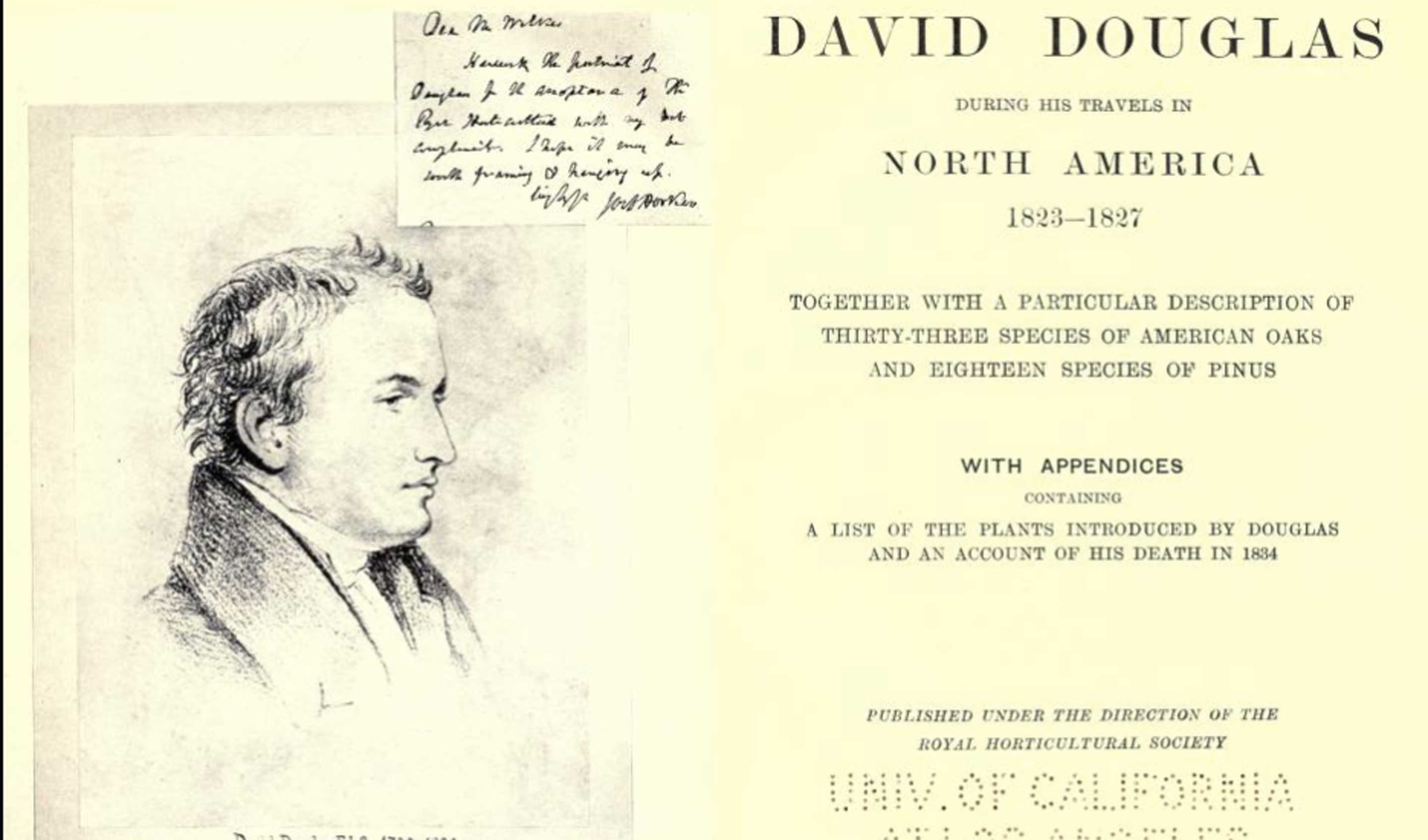

Nineteenth-Century naturalists scoured the Pacific Northwest seeking out new “discoveries” of flora and fauna to record and send back to scientists and collectors in Great Britain, Europe and the Atlantic seaboard. Lewis and Clark’s journals piqued the curiosity of naturalists worldwide. One of the best known was the young Scot David Douglas who arrived at Fort Vancouver in May 1825, and remained two years hiking over 10,000 miles with his little dog Billy and various native guides north across Canada, east to the Rocky Mountains, south to Santa Barbara, CA. The naturalists’ searches contributed greatly to descriptions of the native habitats as they journeyed through virtually untouched landscapes before the 1830s. They often advised Hudson’s Bay Company employees and settlers regarding nonindigenous plants and animals that could be successfully introduced to the land. Little heed was given to the traditional plants and animals that were a part of Indian lifestyles; most newcomers were farmers and traders, eager for change all around. Many of the newcomers preferred meat or fowl to fish, and the powerful salmon, a cultural staple and tribal commodity, was viewed more as a potential export product than as the staff of life for Euro-Americans.

David Douglas’ Journal: March 20, 1826

“Having resolved to devote a season in the interior parts of the country skirting the Rocky Mountains, Dr. McLoughlin, who was unremitting with his kind attentions, allowed me to embark in the spring boat for the interior with two reams of paper, which was an enormous indulgence. Rather than go unprovided in this respect I curtailed the small supply of clothing. We reached the falls on the 24th. From this point to Wallawallah, the first inland post, the country is hilly, destitute of timber, the soil sandy and barren, the banks of the river rocky. I walked along the banks of the river save when the boat was under sail, and, though early in the season, added some plants to my collection – the beautiful Lilium pudicum Pursh, Beargrass,[1] two new genera of Cruciferae [mustard family], and Ribes cereum [wax currant]; but what gave me most pleasure was finding a new species of Wulfenia. The banks of the river as high up as the junction of Spokane River are steep, bold and rocky, the river rapid and difficult to ascend. This part of the country is barren, sandy soils and very parched. A few deer C[ervus] leucurus, bears, wolves, foxes and badgers are occasionally seen among the brushwood, which consists principally of Purshis tridentate and Artemisia arborea [sic]. The principal of the feathered tribe are Tetrao urophasianus and T. urophasianellus [sage grouse], at this season of the year celebrating their nuptials on the gravelly shores of the streams. In several contracted parts of the river, where the breadth does not exceed 200 yards, the water during the melting of the snow rises to the amazing height of 43 feet perpendicular above its ordinary level.”

You can read his full journal at the Internet Archive.

End Notes

[1] Baker, “Xerophyllum asphdeloides, var.,” in Journal Linnean Society xvii. UK: Antiquarian Press, 1959. 62, 467.